In late 2019, the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission (Hubei Province, China) reported an outbreak of pneumonia cases, which were subsequently identified as being caused by a novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2. A month later, the World Health Organization (WHO) formally declared the outbreak in China to be a public health emergency of international concern. Two months after that, the same organization officially characterized the new outbreak as COVID-19 (coronavirus disease), a rapidly spreading pandemic worldwide WHO, 2020;Sandín et al., 2020, while simultaneously issuing a statement recommending common-sense safety measures WHO, 2020. COVID-19 is caused by the coronavirus (CoV), a family of viruses that affects the respiratory system and can cause both mild and severe respiratory illnesses.

It is part of a group of RNA viruses that affect humans and animals PAHO, 2020, leading to symptoms such as runny nose, sneezing, sore throat, fever, fatigue, dry cough, diarrhea, shortness of breath, coughing up blood, headache, loss of smell, and lymph node enlargement. The pathogenesis caused by COVID-19 primarily involves severe pneumonia and acute cardiac injuries Rothan & Byrareddy, 2020.

During March 2020, as Europe was identified as the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic, Argentina reported its first death from the virus, marking the onset of the pandemic in Latin America (Wikipedia, 2020). Similarly, in that same month, prior to the detection of the first two cases of COVID-19, the government of Bolivia declared a national emergency on March 11th following the first death caused by the disease CARITAS, 2020.

The unprecedented nature of this new health threat, coupled with widespread confusion regarding the necessary measures for the populace, prompted governments to implement various restrictive biosafety measures, including quarantine and social distancing. Concurrently, the WHO disseminated a series of psychological measures to the global population to address the pandemic WHO, 2020. Consequently, for several months thereafter, individuals remained at home, abstaining from most social interactions, thus adopting an altered lifestyle far removed from their usual routines and social connections.

This new reality, characterized by isolation as a way of life, confronted humanity with feelings of loneliness, fear, uncertainty, and confusion-psychological challenges that we typically strive to avoid. Furthermore, in addition to confinement, labor restrictions, and financial threats, which evoked parallels to past global conflicts and catastrophes Camelo-Avedoy, 2020; ECLAC, 2020), access to education was severely curtailed as well Gallego et al., 2020. These circumstances compelled individuals to navigate the sharing of love, food, work, leisure, and education within the confines of a single space.

Indeed, the circumstances surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic transformed our homes into a global institution in the purest sense as conceptualized by Goffman (1972), with consequences that are both profound and unpredictable.

Loneliness and psychological disorders

There is a wealth of scientific evidence regarding the correlation between social isolation and emotional distress Orellana & Orellana, 2020;Sandín et al., 2020. Recent studies indicate that perceived social isolation or loneliness poses a risk factor for cognitive performance Cacioppo & Hawkley, 2009;Cacioppo, Hawkley, & Thisted, 2010 and leads to adverse effects on the well-being of individuals with psychological issues, including depression, anxiety, and anger Abad, Fearday, & Safdar, 2010, particularly among older adults Saito, Kai, & Takizawa, 2012;Courting & Knapp, 2017;Taylor et al., 2016. Ge, Yap, Ong, & Heng (2017) demonstrated that social isolation resulting from poor connections with relatives and friends, as well as loneliness, was associated with depressive symptoms, even after adjusting for age, sex, employment status, and other covariates. Additionally, social isolation has been linked to increased morbidity and mortality among affected individuals Teo, 2013;Klinenberg, 2016;Holt-Lunstad et al., 2015.

Addressing Altered Emotional States

The available literature also suggests that certain psychological factors, expressed in the form of personal abilities or behavior patterns, can mitigate the impact of anxiety and depression. For instance, Samani, Jokar & Sahragard (2007) demonstrated that resilience enhances life satisfaction while reducing levels of negative emotions. Similarly, a study conducted by Steensma, Heijer & Stallen (2007) reported the positive effects of a resilience training program in alleviating chronic health disorders resulting from burnout among employees.

Soltani et al. (2013) found correlations between resilience, cognitive flexibility, coping skills, and depression, with resilience demonstrating a significant mediational effect in reducing depression and other emotional responses. Conversely, Fedina et al. (2017) concluded that resilience could mitigate symptoms of depression and anxiety associated with interpersonal violence, although they cautioned that these effects may vary based on ethnic characteristics. Recent studies have also yielded similar results regarding the influence of resilience on depression Wu et al., 2017;Ding et al., 2017;Poole, Dobson & Pusch, 2017.

Resilience has been effectively utilized to moderate the relationship between adverse childhood experiences and adult depression Poole, Dobson & Pusch, 2017. Recent studies conducted within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic have also demonstrated the efficacy of resilience in moderating the impact of stress on depression symptoms Havnen et al., 2020 and sleep disturbances Grossman, Hoffman, Palgi & Shrira, 2020. Furthermore, resilience has been identified as a crucial moderating variable in various behavioral alterations across different population groups, including its role in mitigating ostracism and depression (Geng-Feng et al., 2016), anxiety and loss of sense of life (Smedema & Franco-Módenes, 2018), obsessive-compulsive symptoms Hjemdal et al., 2011, as well as various altered personality traits Shi, Liu, Wang & Wang, 2015.

Similarly, empirical evidence supports the buffering role of self-efficacy in relation to depression and other affective disorders. For example, Weng et al. (2008) found that self-efficacy was negatively associated with depressive symptoms in surgical patients. Jun-Pu, Hou & Ma (2017) investigated the impact of self-efficacy on depression and confirmed, through Structural Equation Modeling, the mediating role of dispositional optimism. Other studies have explored the effects of self-efficacy on stress from the perspective of the sympathetic nervous system O'Leary, 1992, anxiety disorders in adolescents Muris, 2002, and the attenuation of depression Maddux & Meier, 1995;Bandura et al., 1999;Ehrenberg, Cox & Koopman, 1991;Maciejewski, Prigerson & Mazure, 2000;Haslam, Pakenham, & Smith, 2006.

Consequently, there has been a growing emphasis on the significant attenuating role played by both self-efficacy and resilience in addressing a range of issues associated with individuals' psychological well-being. For instance, in the case of self-efficacy, Zhang & Jin (2016) found that high self-efficacy serves as a protective factor against postpartum depression. Tonga, Eilertsen, Solem, Arnevik, Korsnes, & Ulstein (2020) suggested that greater self-efficacy may positively impact the quality of life of patients with cognitive impairments and moderate dementia, partially reducing depression and anxiety. Liu, Xu, & Wang (2017) successfully moderated self-efficacy to alleviate physical ailments. Tu & Zhang (2015) proposed that self-efficacy acts as a mediator in the relationship between loneliness, stress, and life satisfaction, while Patrão, Alves & Neiva (2019) found a strong negative correlation between high levels of self-efficacy in the elderly and depression, as well as in the relationship between positive humor and cognitive performance Niemiec & Lachowicz-Tabaczek, 2015.

Similarly, Tapia, Iturra, Valdivia et al. (2017) reported that self-efficacy helped older adults promote and maintain behaviors conducive to a healthier life. Similar results were observed by Tuğba (2016), where self-efficacy moderated the attitudes of young people towards peace and hope, in the modulation of problems related to work stress Grau, Salanova & Peiró, 2001, in the relationship between stress and job exhaustion or burnout Makara-Studzińska, Golonka & Izydorczyk, 2019, in moderating the relationship between self-esteem and job insecurity Adekiya, 2018, and in alleviating anxiety stemming from training Saks, 1994.

The present study

The purpose of this research was to investigate the psychological consequences of prolonged quarantine-induced confinement among a representative adult sample of Bolivians of both genders. Specifically, it aimed to explore individuals' perceptions of their emotional states-fears, anxieties, and depressions-while subjected to social confinement, a measure implemented by the national government to mitigate the spread of COVID-19. Additionally, the study aimed to examine the moderating effects of resilience and self-efficacy, given their known capacity to mitigate the impacts of psychological distress.

The following research questions guided the study:

a) How and to what extent is the loneliness experienced during quarantine confinement related to affective and emotional manifestations such as depression, anxiety, and stress?

b) Can perceived loneliness, stress, and anxiety serve as predictors of depressive reactions in conditions of social confinement?

c) Given the characteristics described above, what is the moderating capacity of resilience and self-efficacy in attenuating the influence of perceived loneliness on depression and anxiety during quarantine confinement?

Based on these research questions, the hypotheses formulated within the theoretical framework were as follows:

H1: High levels of perceived loneliness resulting from social isolation measures to prevent COVID-19 contribute significantly to increased levels of stress, anxiety, and depression among individuals subjected to confinement.

H2: The states of loneliness, anxiety, and stress induced by confinement during quarantine can predict depression.

H3: Personal skills related to resilience and self-efficacy will act as mitigating factors in the effect of both loneliness and anxiety or depression.

METHOD

Sample and participants.

The current study utilized a non-probabilistic sampling method comprising 596 participants. Participants were recruited through an online survey administered via the Google Forms platform. Recruitment was facilitated through social media channels, where individuals were provided with a link to access the survey instruments. Participation in the survey was voluntary, and individuals who chose to participate implicitly consented to the study procedures. Furthermore, comprehensive information regarding the aims and nature of the research was provided in the instructions section to ensure informed participation.

The study gathered data from various cities across Bolivia, including La Paz (n = 472, 79.2%), Oruro (n = 46, 7.7%), Cochabamba (n = 30, 5%), Santa Cruz de la Sierra (n = 27, 4.5%), and to a lesser extent from other cities in the country (n = 21, 3.6%). Most participants (95.5%) resided in urban areas, with the remaining 4.5% residing in rural areas. Participants' ages ranged from 18 to 75 years, with a mean age of 31.36 years and a standard deviation of 12.832. The sample consisted of 64.9% females (n = 387) and 35.1% males (n = 209). A significant proportion of participants belonged to the middle or upper-middle-income class (n = 459, 77%) and lived in residences with three or more rooms. Approximately 6.9% of the sample (n = 41) reported being unemployed at the time of the survey.

Instruments

The study gathered data from various cities across Bolivia, including La Paz (n = 472, 79.2%), Oruro (n = 46, 7.7%), Cochabamba (n = 30, 5%), Santa Cruz de la Sierra (n = 27, 4.5%), and to a lesser extent from other cities in the country (n = 21, 3.6%). Most participants (95.5%) resided in urban areas, with the remaining 4.5% residing in rural areas. Participants' ages ranged from 18 to 75 years, with a mean age of 31.36 years and a standard deviation of 12.832. The sample consisted of 64.9% females (n = 387) and 35.1% males (n = 209). A significant proportion of participants belonged to the middle or upper-middle-income class (n = 459, 77%) and lived in residences with three or more rooms. Approximately 6.9% of the sample (n = 41) reported being unemployed at the time of the survey.

UCLA Loneliness Scale Reduced - Spanish versionVázquez-Morejón & Jiménez-García, 1994: This instrument features a unifactorial structure consisting of 4 items, each measured on a four-point scale: frequently (1), sometimes (2), rarely (3), and never (4). Scores are obtained by summing the item scores, with higher scores indicating greater loneliness. The internal consistency for the four items demonstrates an Alpha coefficient of .749, and the test-retest correlation for total scores was found to be r = .7056 (N = 33, p < 0.01). Concurrent validity, as assessed by correlation with the Beck Depression Inventory, yielded an acceptable result (N = 42, r = .4698, p < .01). Additionally, the correlation between scores of the abbreviated and complete forms was r = .9084 (N = 86, p < .01) Vázquez-Morejón & Jiménez-García, 1994.

Perceived Stress Scale PES14 - Spanish adaptationLarzabal-Fernandez & Ramos-Noboa, 2019: This scale, adapted from the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) developed by Cohen, Kamarck, and Mermelstein (1983), comprises 14 items designed to measure perceived stress over the past month. Responses are provided on a five-point scale: Never (0), Almost never (1), Occasionally (3), Often (4), and very often (5). A higher score indicates a greater level of perceived stress. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) suggested two factors, which together explained 41.94% of the total variance. The general reliability of the PES-14 yielded an Alpha coefficient of .617, with Alphas ranging between .805 and .811 for each of the two proposed dimensions (coping with stressors and perception of stress).

Generalized Anxiety and Depression Disorder Scale (GAD-7) - Spanish adaptation García-Campayo et al., 2010: The GAD-7, originally developed by Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams, and Löwe (2006), was adapted into Spanish by García-Campayo et al. (2010). This scale demonstrates good reliability, with a Cronbach's Alpha coefficient of 0.936. Additionally, all items exhibit inter-item correlations greater than 0.68, with a test-retest correlation coefficient of 0.844 and an intra-class correlation coefficient of 0.926 (95% confidence interval: 0.881-0.958).

Brief Resilient Coping Scale (BRCS) - Spanish adaptationLimonero et al., 2012: The Spanish version of the BRCS, adapted from the original scale developed by Sinclair and Wallston (2004), consists of four items designed to assess stress coping in highly adaptive environments. The scale employs a five-point response format ranging from 1 ("does not describe you at all") to 5 ("describes you very well"). Total scores on the scale range from 4 to 20, with higher scores indicating greater adaptability. The original BRCS demonstrated reliability through internal consistency (Cronbach's Alpha = .680) and test-retest correlation (r = .71). Significant correlations were observed between the BRCS and other measures of personal coping, indicating good validity Sinclair & Wallston, 2004.

The Spanish adaptation of the BRCS followed a translation/back-translation procedure recommended by the Scientific Advisory Committee "Medical Outcomes Trust" (2002). Authors conducted Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) to confirm that a single latent factor (resilient coping) accounted for the variance and covariance between the four items. The fit indices obtained were satisfactory: χ2 = 3.04 with 2 degrees of freedom (p = .21), CFI = .99, GFI = .99, NNFI = .98, SRMR = .01, and RMSEA = .04 [90% CI = (.00 - .11)].

Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale (GSS): The GSS, originally developed by Jerusalem and Schwarzer (1992), has been studied comparatively in five countries (Costa Rica, Germany, Poland, Turkey, and the United States) by Luszczynska & Gutiérrez-Doña e) Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale (GSS): The GSS, originally developed by Jerusalem and Schwarzer (1992), has been studied comparatively in five countries (Costa Rica, Germany, Poland, Turkey, and the United States) by Luszczynska & Gutiérrez-Doña (2005). It consists of 10 items rated on a 4-point Likert scale, yielding total scores between 10 and 40 points. The authors reported acceptable reliability coefficients for the scale.

According to the original structure of the scale, the GSS is expected to be related to constructs described in personality theories concerning self-regulatory beliefs. Optimism, self-regulation, self-esteem, and orientation towards the future have been found to be positively associated with the GSS, with coefficients ranging from moderate to low.

There is a significant, positive, and strong relationship between GSS and self-regulation. Moreover, the GSS has been found to be negatively related to inventories assessing anxiety, depression, anger, and negative affect. Quality of life is positively correlated with self-efficacy, with significant relationships characterized by low to moderate coefficients.

(2005). It consists of 10 items rated on a 4-point Likert scale, yielding total scores between 10 and 40 points. The authors reported acceptable reliability coefficients for the scale. According to the original structure of the scale, the GSS is expected to be related to constructs described in personality theories concerning self-regulatory beliefs.

Optimism, self-regulation, self-esteem, and orientation towards the future have been found to be positively associated with the GSS, with coefficients ranging from moderate to low. There is a significant, positive, and strong relationship between GSS and self-regulation. Moreover, the GSS has been found to be negatively related to inventories assessing anxiety, depression, anger, and negative affect. Quality of life is positively correlated with self-efficacy, with significant relationships characterized by low to moderate coefficients.

Procedure

Once the battery of suitable tests for studying the identified variables was established, it was adapted to the Google Forms format for self-administration online via this platform. The tests were administered over approximately 10 days during the initial phase of the health emergency in Bolivia, corresponding to the period of strict quarantine. After debugging the dataset, it was analyzed using the SPSS statistical program to generate the results described below.

Analysis decisions. Based on the data exploration findings, which indicated relatively normal distributions with slight positive and negative skewness and kurtosis (skew values between .313 and .842, and kurtosis values between .086 and 1.081), as well as acceptable central tendency estimators and results of the Kolmogorov-Smirnoff normality tests, robust parametric statistical tests were deemed appropriate. Additionally, assuming homoscedasticity was justified.

RESULTS

The investigation aimed to examine the repercussions of quarantine confinement on various psychological outcomes. Thus, the first step was to assess the relationship between perceived loneliness imposed by quarantine and the variables of depression, anxiety, and stress.

Table 1. Bivariate correlations between the variables of the present study

** The correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (bilateral)

Table 1 displays the relationships between perceived loneliness, stress, anxiety, depression, resilience, and self-efficacy. Perceived loneliness is found to be positively and significantly correlated with stress and depression, indicating that higher levels of perceived loneliness are associated with increased levels of stress and depression.

Furthermore, resilience exhibits a strong negative correlation with perceived loneliness, stress, anxiety, and depression. Similarly, self-efficacy demonstrates negative correlations with perceived loneliness, stress, anxiety, and depression. All correlations are highly significant (p < .001). These findings suggest that as resilience and self-efficacy increase, levels of stress, anxiety, and depression decrease significantly and consistently.

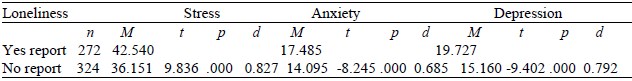

Groups comparisons. Table 2 presents the results of the comparisons between groups based on the presence and absence of loneliness, stress, and anxiety on depression, using the t-test for independent samples.

Table 2. Difference of depression means in three groups of participants who reported and did not report loneliness, stress and anxiety.

The results presented in Table 2 strongly suggest that the conditions of loneliness imposed by quarantine, the experienced stress during the period of forced isolation, and the presence of associated anxiety have a notable effect on the manifestations of depression reported by the participants in the present investigation. Additionally, comparisons between groups that reported and did not report loneliness revealed greater expressions of stress, anxiety, and depression in the former group.

Furthermore, as depicted in Table 3, comparisons of means using Student's t-test consistently revealed highly significant differences in favor of the group reporting perceived loneliness. Moreover, the effect sizes observed in all three cases are deemed acceptable.

Table 3. This table displays the means and standard deviations for each group, as well as the results of the t-test for independent samples, including significance levels and effect sizes.

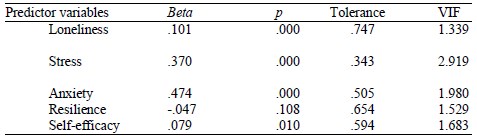

Predictive analysis. A multiple linear regression model was employed to assess the predictive potential of the variables (loneliness, stress, anxiety, resilience, and self-efficacy) with respect to depression as the criterion variable. Utilizing the "enter" method, a significant model was obtained (F(6, 589) = 199.003, p < .001) with an adjusted R-squared value of .666, indicating that approximately 66.6% of the variance in depression can be explained by the included variables.:

As shown in Table 4, four out of the five modeled variables (loneliness, stress, anxiety, and self-efficacy) are deemed to be good predictors of depression. Additionally, the table indicates that the model is not invalidated by multicollinearity, suggesting that the included predictors are relatively independent of each other and contribute uniquely to the prediction of depression.

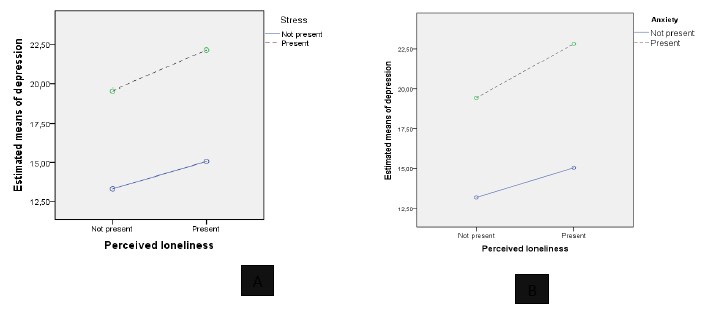

Analysis of Variance. Next, a two-way ANOVA was conducted to examine whether the combined influence of perceived loneliness and stress, as well as perceived loneliness and anxiety experienced during quarantine confinement, had significant effects on depression. The results are depicted in Figure 1A-B.

Figure 1A and B. Effects of the influence of the perception of loneliness and stress; and the perception of loneliness and anxiety, obtained with two-way analysis of variances.

In the case of the joint action of loneliness and stress, stress was found to significantly influence depression (F Stress 1/593 = 242.20, p < .001). It is notable that as participants reported higher levels of stress, depression was experienced with greater intensity. Similarly, loneliness was shown to have a significant effect on depression, with participants reporting higher levels of loneliness experiencing greater depressive responses (F loneliness 1/593 = 25.570, p < .001).

However, the ANOVA did not reveal significant interaction effects between both factors. Figure 1-A visually represents these outcomes.

In the case of the loneliness-anxiety combination, the results were notably similar: anxiety appeared to exacerbate depression (FAnxiety 1/593 = 299.722, p < .001), as did the perception of loneliness (Floneliness 1/593 = 41.662, p < .001). However, similar to the previous case, both factors did not interact to produce a joint effect on depression (Figure 1-B). Moderation analysis. The present investigation also explored the moderating role of the variable’s "resilience" and "self-efficacy" on the predicted relationship between anxiety-depression and perceived loneliness-depression. In other words, given the predictive influence of anxiety and loneliness on depression, it was necessary to verify whether both resilience and self-efficacy could moderate these relationships, confirming their attenuating effect.

The predicted models could assume the characteristics suggested in Figure 2:

Figure 2. Models representing the moderating influences (by attenuation) of resilience and self-efficacy, on the anxiety-depression and perceived loneliness-depression relationships.

The moderating capacity of the resilience and self-efficacy variables was studied based on four models:

a) The first model investigated the attenuation of resilience on the anxiety-depression relationship.

b) The second model analyzed the attenuating capacity of self-efficacy on the anxiety-depression relationship.

c) The third model modeled the attenuating function of resilience on the perception of loneliness-depression relationship.

d) Finally, the fourth model verified the effect of attenuation of self-efficacy on the loneliness-depression relationship.

A multiple linear regression moderation model (MRLM) was proposed to evaluate the effect of resilience on the demonstrated prediction of the anxiety-depression variable (β = .474, p < .000).

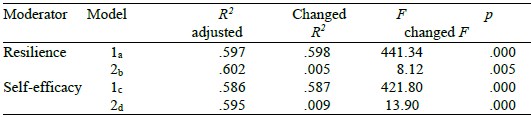

Table 5 The regression model explored the change in R 2 values due to moderating variables, resilience, and self-efficacy, on the prediction of anxiety-depression.

a. Predictors: (Constant), Z score: Resilience, Z score: Anxiety

b. Predictors: (Constant), Z score: Resilience, Z score: Anxiety, Resilience Moderation

c. Predictors: (Constant), Z score: Self-efficacy, Z score: Anxiety

d. Predictors: (Constant), Z score: Self-efficacy, Z score: Anxiety, Self-efficacy Moderator

In the second model, both resilience and self-efficacy showed small but significant changes in R2 values. This indicates a modification in the percentage of variance explained for the moderating effects of resilience and self-efficacy (β resilience = -0.075, p < 0.005, and β self-efficacy = -0.098, respectively). Additionally, both variables significantly predict the dependent variable, indicating their individual contribution to the prediction of depression (β resilience = -0.136, p < 0.000; β self-efficacy = -0.090, p < 0.002).

Figure 3A-B. Moderating effect of resilience and self-efficacy on the proven anxiety-depression relationship, expressed in standardized values.

As depicted in Figure 3A-B, both variables act as moderators by attenuating the influence of anxiety on depression. This finding suggests that individuals experiencing anxiety as a result of prolonged social confinement may decrease their depressive reactions if they exhibit resilience and/or self-efficacy. These personal competencies serve as protective factors, mitigating the psychological vulnerability induced by extended quarantine.

Table 6. Summary of the regression model exploring the change in R 2 values because of both moderating variables on prediction of perceived loneliness -depression.

a. Predictors: (Constant), Z score: Resilience, Z score: Loneliness

b. Predictors: (Constant), Z score: Resilience, Z score: Loneliness, Moderating Resilience -Loneliness

c. Predictors: (Constant), Z score: Self-efficacy, Z score: Loneliness

d. Predictors: (Constant), Z score: Self-efficacy, Z score: Loneliness, Moderating Self-efficacy - Loneliness

In Table 6, the results of the moderation process for both variables regarding the perceived loneliness-depression relationship are presented. These values closely resemble those reported for the anxiety-depression relationship. Small yet statistically significant changes in R2 are observed, confirming alterations in the explained variance due to the moderating effect of resilience and self-efficacy, respectively (β resilience = -0.082, p < 0.018; β self-efficacy = -0.102, p < 0.003). Additionally, both variables significantly predict depression (β resilience = -0.311, p < 0.000; β self-efficacy = -0.276, p < 0.000). Figure 4A-B provides visual inspection of the moderation process results.

Figure 4A-B Moderation effect of resilience and self-efficacy on the perceived loneliness - depression relationship, expressed in standardized values. Figure 4A-B illustrates the attenuation effects of both variables on the impact of perceived loneliness on depression, serving a protective function amidst the crisis induced by enforced isolation during the COVID-19 quarantine.

DISCUSSION

This research delved into the psychological ramifications of social confinement during stringent quarantine, particularly focusing on stress, anxiety, and depression. As articulated by Waal (2007), the significance of the study is firmly established: "A good example of the fully social nature of our species is that, after the death penalty, the most extreme punishment we can conceive of is solitary confinement. And this is so, without a doubt, because we were not born for loners. Our bodies and our minds are not designed to live in the absence of others. We get depressed without social support: our health deteriorates. In a recent experiment, healthy volunteers who were deliberately exposed to a cold and flu virus became ill more easily if they had few friends and family around them Cohen et al., 1997.

Although women naturally understand the primacy of connection with others - perhaps because for 180 million years, mammalian females with tendencies that prioritize caring for others have reproduced more than those without such tendencies - the same can be applied to men. In modern society there is no more effective way for men to extend their life horizons than to marry and stay married: it increases their life expectancy beyond 65 by between 65 and 90% Taylor, 2002) (De Waal, 2007, p 28)." Consequently, the aim was to ascertain the distressing effects of perceived loneliness experienced to varying degrees among a sample of Bolivian adults.

The research confirmed a strong and positive correlation between the variables under study: heightened levels of perceived loneliness correlated with elevated levels of stress, anxiety, and depression among individuals subjected to social confinement. Moreover, significant discrepancies were identified in the manifestation of stress, anxiety, and depression based on the degree of loneliness reported by the sample.

The confirmation of these relationships led to the rejection of our first null hypothesis, which posited that elevated levels of perceived loneliness induced by enforced confinement do not contribute to heightened affective or emotional disturbances among those experiencing it. Similarly, it became evident that loneliness, anxiety, and stress serve as reliable predictors of depression in conditions of mandatory isolation, thereby refuting the second null hypothesis. Finally, it was established that both personal resilience and self-efficacy act as moderators, attenuating the documented effects of loneliness and anxiety on depression. This finding enabled us to reject the third null hypothesis as well.

These results align with findings from previous studies regarding the impact of anxiety on depression across different age groups Rahman, Bairagi, Dey & Nahar, 2017, as well as the emotional repercussions of withdrawal from familial support structures during periods of isolation, such as those imposed by the pandemic Huarcaya-Victoria, 2020;Ramirez-Ortiz et al., 2020.

Moreover, the outcomes of this investigation are consistent with recent research. For instance, Gerino, Rolle, Sechi & Brustia (2017) and Poole, Dobson, & Pusch (2017) reported that resilience positively influenced individuals' ability to cope with loneliness and depression. Similar findings have been observed in studies examining the impact of resilience on mitigating anxiety, stress, and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic Havnen et al., 2020;Barzilay et al., 2020;Cao et al., 2020, as well as its role in alleviating loneliness-associated sleep disturbances Grossman et al., 2020 and enhancing students' sense of purpose Smedema & Franco-Módenes, 2018.

The findings of this study underscore the importance of self-efficacy in buffering the relationship between loneliness/anxiety and depression, echoing similar research Tonga et al., 2020;Al-Khatib, 2012;Tu & Zhang, 2015. These results suggest potential avenues for intervention to mitigate the adverse effects of prolonged isolation and its impact on depressive symptoms.

One implication of these findings is the development of clinical protocols tailored to individuals vulnerable to depression, focusing on enhancing resilience and self-efficacy. Interventions aimed at bolstering these competencies could serve as protective factors against depression, especially in times of heightened stress and social isolation.

However, it's essential to acknowledge the limitations of this study. Online sampling may have introduced biases toward groups with greater access to digital resources and higher levels of digital literacy. Additionally, the study lacked precise control over the extent of participants' objective isolation. Furthermore, reliance on self-reported measures may not fully capture diagnostic accuracy, and the reliability and validity of these instruments warrant further investigation.

Therefore, while these findings offer valuable insights, caution is warranted in interpreting them. Future research should strive to address these limitations to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the relationships explored in this study and to ensure the validity and generalizability of the results.