1. Introduction

Technological advances have eased the development of electronic payment instruments. Their use, according to statistics, has increased in recent years. On the African continent, for example, the use of mobile wallets associated with the users' cell phone line is important, considering that access to formal banking entities is somewhat more difficult in that región and that the use of cell phones instead, is fully disseminated.

Payments through electronic fund transfers, meanwhile, have increased with the development of safe web portals and, more recently, with applications developed by banks that can also be used from mobile phones.

In the Bolivian context, immediate payments with QR codes are a recent innovation, initially introduced as a simpler and faster way to make interbank transfers. These payments began to be used in 2019 and increased exponentially during the months of coronavirus lockdown in 2020. Once mobility restrictions ceased, the use ofthese payments has remained dynamic and appears to have motivated people to open bank accounts or at least have a mobile wallet, which in Bolivia does not require a bank account.

On the other hand, the informal economy in Bolivia is important and although there are not many studies that precisely measure its size, it seems to frequently host transactions with QR payments.

In this sense, this research document aims to identify QR immediate payments usage at the Barrio Lindo fair in the municipality of Santa Cruz de la Sierra, and whether costumers or merchants have been encouraged to open bank accounts to speed up payments. Likewise, the research explores the advantages and disadvantages that users perceive about these payments, the main reasons why they do not use them and propose, if appropriate, actions for the government and/or for the entities that provide payment services.

The results of the field work carried out suggest that there is an important use of QR payments among costumers, although cash continues to be the main instrument to make their purchases. The main advantages of QR immediate payments are quickness, safety and that there is no cost associated to its use. On the merchants' side, more than 80% accept cash and QR payments, highlighting the speed with which it is possible to receive sales payments as the main positive characteristic and the interruption or delays of internet service providers as the main negative characteristic identified.

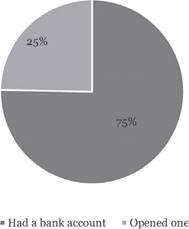

Regarding banking usage, almost half of the costumers indicate that they opened a bank account to perform QR payments. This percentage is lower in the case ofmerchants, only 25% opened an account. This is probably because they are engaged in commercial activity and thus it is more likely that they had a bank account even before the availability of QR payments.

The document is organized as follows: after this introduction, the following shows the importance of electronic payments in Bolivia and a compilation of the empirical evidence found in this regard, section 3 presents some general characteristics of the Bolivian economy, highlighting its high degree of informality, and the Barrio Lindo fair in particular. Section 4 shows the methodology followed and the results of the field work carried out during the research. Conclusions and future challenges are presented in section 5.

2. Electronic payments in Bolivia

A payment system is a set of instruments, banking procedures and, generally, fund transfer systems that ensure the circulation of money (Banco de México, 2023). Payment instruments are all those documents or devices that allow the transfer of money, banking procedures involve the set ofsteps that the agents involved in the circulation ofmoney will follow (Banco de Pagos Internacionales, 2003).

The most basic payment system is the one that uses cash as a payment instrument. Banking procedures indicate the characteristics ofbanknotes and coins, as well as the requirements that must be met for their acceptance by users and subsequent circulation. With the passage of time and technological advances, electronic payment instruments emerged as an alternative to cash.

According to the Regulation of payment services, electronic payment instruments, clearing and settlement (Banco Central de Bolivia, 2022), electronic payment instruments are defined as electronic devices or documents that can be used physically or virtually so that the user can initiate a payment order and make inquiries about the movements made with the instrument. The regulations provide for three electronic payment instruments: mobile wallet, Electronic Fund Transfer Orders (OETFs) and electronic cards (debit, credit and prepaid).

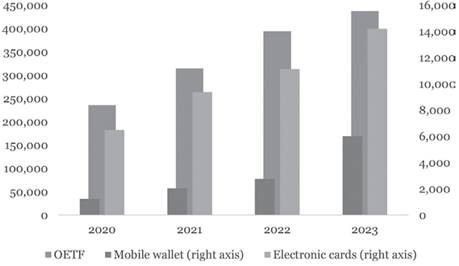

Figure 1 shows recent evolution of electronic payment instruments in Bolivia. The value of payments with these instruments increased significantly, from Bs. 245,623 million in the period January - August 2020 to Bs. 459,643 million in the same period of 2023. This

significant increase implies that the value ofpayments with these Instruments almost doubled between 2020 and 2023.

Source: Banco Central de Bolivia (2023a).

Figure 1: Processed value with electronic payment instruments (in millions of Bs, January to August of each year)

The value of payments is determined mainly by OETFs, which represent an average of 95.8% of the total. Together, payments with mobile wallets and cards represent a value ofless than 5%. It should be noted that OETFs had significant increases in years 2021 and 2022 with growth rates that were around 30% in each year.

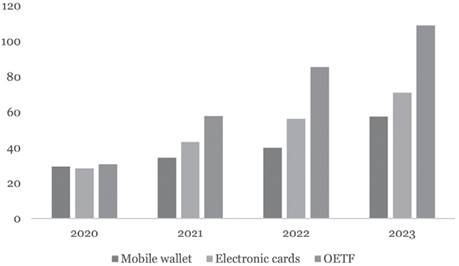

The use of OETFs as an electronic payment instrument is also evident in the number of operations carried out in recent years. Having processed around 31 million orders in the first eight months of 2020, with a similar participation for mobile wallets and electronic cards, in the period January - August 2023 the number of OETFs processed reached Bs. 109 million. This figure represents more than three times the number ofoperations in the analyzed period of 2020. The number of operations with mobile wallets and cards also increased, but in a much more modest way compared to the number of operations with OETFs (Figure 2).

Source: Banco Central de Bolivia (2023a).

Figure 2: Number of operations with electronic payment instruments (in millions, January to August of each year)

The growing increase in the value and volume of operations with electronic payment instruments was initially influenced by mobility restrictions resulting from health measures against the coronavirus. Once these restrictions were lifted, the use of these payment instruments continued to increase, mainly due to the acceptance that OETFs had.

According to the Payment System Surveillance Report (Banco Central de Bolivia, 2023b), the factors that contribute to explain the growing use of OETFs are related to the developments carried out by financial intermediation entities to facilitate the use of internet and mobile banking applications and, mainly, the introduction of QR payments in 2019. The aforementioned report indicates that in 2022, 38 million payments were made with QR for a value of Bs. 19,180 million, which represented 3% of the value of payments with OETFs in that year. The number of QR payments, on the other hand, represented 27% of the total number of OETFs.

QR immediate payments introduce efficiency in the payment process since both the originator and the recipient can generate a QR code for collection or payment to the other party through their mobile application, reducing to zero the possibility of errors related to the account number of the recipient. Both parties can see, online, the movements in their accounts with their respective mobile banking applications.

The ease with which it is possible to pay with QR codes allows its use not only in everyday transactions, but also in those of a commercial nature, particularly for microbusinesses and small businesses, which have great relevance in the Bolivian economy.

Beyond official statistics, few studies have been found on the use of electronic payments and in particular on QR immediate payments.

In general, according to a study on financial inclusion in eight Latin American countries, 80% of people know electronic cards and 53% know payment applications and mobile wallets, with an increase of 24 percentage points between 2023 and 2021. Regarding the payment methods used to pay for goods and services, the aforementioned study finds that 97% ofpeople use cash, 11% use financial institution applications, and 14% use mobile wallets and payment applications. In the case of Bolivia, it stands out that 27% of the population use banked means (any alternative payment instrument to cash), in contrast to the 37% found for the region. Similarly, the frequency of using banked means in Bolivia is 2.53 times per month while in Latin America it is 6.76 times (Grupo de Crédito S. A., 2023).

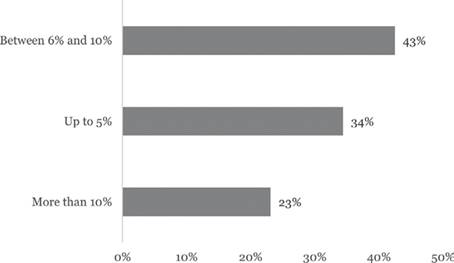

Laserna (2022) investigates the infrastructure available in Bolivia that could facilitate the transition to a cashless economy, as well as the perceptions of the population about virtual payment facilities that exist in the country. The author carried out, with the support of the Center for Studies of the Economic and Social Reality of Cochabamba and the company Datacción SRL, telephone surveys in the main cities of Bolivia during September 2021.

The main results show that 54% of the population does not have a bank account and their knowledge about establishments that allow cashless payments is relatively low (less than 30% on average). The case of Santa Cruz stood out, whose population has the highest percentage of people who know businesses where it is possible to pay without cash (36%). When asked, however, about their willingness to use digital payment methods, the percentages increase considerably (Figure 3).

Source: Laserna (2022).

Figure 3: Knowledge and willingness to make cashless payments (in percentages)

People who declared they know digital payment methods identified “convenience” as their main advantage and “complexity” as their main disadvantage. According to the author, this last feature opens an opportunity for financial institutions to intensify their financial education and training programs about the use of tools such as mobile banking and internet banking (Laserna, 2022).

From the supply point of view, Risco (2023) analyzes the case of a microfinance entity that did not fulfill its participation in the QR transaction market in selected macro districts of La Paz city The study carried out surveys in the aforementioned districts, to people and businesses. 384 surveys were carried out on people and 130 on businesses. In the case of people, it was found that most payments are made in cash, the preference for QR immediate payments is around 15% and concentrated in the population up to 30 years old. 68% perceive that there are not many businesses that offer QR immediate payments in the city of La Paz.

In the case of businesses, the preference for cash is greater, since 70% of those surveyed indicated that they prefer cash over other payment alternatives. The preference for QR immediate payments maintained its participation among businesses (15%). People's perception of QR payments reduced availability was confirmed since only 22% of businesses indicated offering this mean ofpayment to their customers.

3. The Bolivian economy and the informal sector

3.1. Key aspects of the Bolivian economy

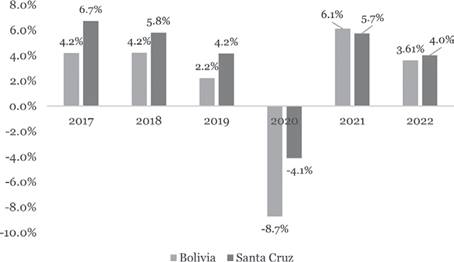

After the lifting ofthe mobility restrictions that characterized the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic, economic activities gradually normalized. However, in 2021 the national economy failed to recover the growth lost during the previous year (6.1% vs. -8.74% in 2020) and during 2022, growth was relatively modest (3.6%). The department of Santa Cruz had a different dynamic, since after declining 4.1%, in 2020 it grew 5.7% in 2021 and 4% in 2022 (Figure 4).

Source: Instituto Nacional de Estadística (2023a,2023c).

Figure 4: Gross domestic product (growth rates, in percentages)

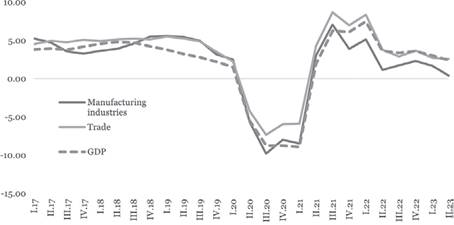

The most recent figures available on growth as ofthe second quarter of 2023 show a more modest national performance, with a twelve-month growth rate ofonly 2.42%, lower than the one at the end of 2022 (3.61%). Sectors related to production and trade activities also showed weak performance, in particular manufacturing industry, which only grew 0.38% compared to the previous twelve months (Figure 5).

It is important to consider that the figures presented only represent a measurement of the country's formal activities, leaving those of an informal nature without a precise statistical record given the methodological difficulties represented by estimating the size of the informal economy.

Source: Instituto Nacional de Estadística (2023b).

Figure 5: Evolution of gross domestic product and key sectors (twelve-month growth rates, in percentages)

3.2. Informality and some specific features of Bolivia

The organization Women in informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing -WIEGO (2023) defines informality as “a set of economic activities, companies, jobs and workers that are not regulated or protected by the market” In 2018, the International Labor Organization released, for the first time, statistics on informal employment, pointing out that 61% of the world’s workers obtain their income from the informal economy (WIEGO, 2023).

Studies on the importance of informality in the workforce or economies are relatively scarce for the Bolivian case. In this context, Medina and Schneider (2018), in a paper on the global informal economy, found that the Bolivian informal economy represented, on average, 62.3% of the gross domestic product during the period 1999-2015. The estimated world average reached 31.9% and Bolivia was one ofthe countries with the highest estimated degree ofinformality.

Velásquez (2020) states that informality occurs due to several factors, highlighting economic factors such as structural changes in an economy, crises, the limited absorption of labor by the industrial sector, etc. Other factors, more related to institutions, refer to the preference that companies have recently shown for so-called “flexible work”, with subcontracting, temporary jobs and others. It has also been argued that the rigid regulation of the formal labor market generates incentives to seek these types of contracts, which are also less costly for companies.

It is important to note that several of the aforementioned economic factors occurred and could have contributed to maintaining an important informal sector in Bolivia. For example, the crisis of the early 1980s, which involved the massive retirement of mining workers due to the fall in the price of tin, the limited industrial development that characterizes the country and the concentration ofproduction in extractive sectors. This has displaced the workforce to trade and services sectors, not only in the formal sector, but also represent the main activities ofthe informal sector of the economy (Valencia, 2020).

Regarding institutional aspects, the times and costs involved in opening a company in Bolivia, the rigid tax regulation and the complex labor legislation would also be driving informality.

3.3. The Barrio Lindo fair

This research selected the Barrio Lindo fair in the city of Santa Cruz de la Sierra to measure the use of QR immediate payments considering the extensive informal sector in Bolivia and the weight ofcommercial activities in the economic structure.

According to former leader Freddy Vega, the Barrio Lindo fair began in 1982 in the center of the city of Santa Cruz de la Sierra (casco viejo). With significant growth in almost twenty years and ten merchant associations the fair was moved to Avenue Brazil and Cuarto Anillo on March 15, 1999 (Barrio Lindo, 2015a).

Barrio Lindo (2015b) points out that the fair “has become one of the largest shopping centers in Bolivia, and the largest and most stocked in Santa Cruz” It has more than 30 associations that bring together around 22,000 merchants with a varied supply in clothing, hardware products, cosmetics and farniture, among others. This wide supply attracts customers from other regions of Bolivia and also from neighboring countries, which would total around two million people visiting the fair.

4. QR immediate payments at the Barrio Lindo fair

4.1. Methodology

In order to measure the use of QR payments at the Barrio Lindo fair, surveys were conducted with customers and merchants. The final versions of the questionnaires used are available upon request. Question attributes were reviewed for clarity, simplicity, and coherence. Likewise, they were discussed with peer colleagues to collect suggestions for improvement.

For the merchant surveys, the figure found in the documentary review, 22,000 merchants, was taken as the population. With a confidence level of 95% and an error of 5%, a sample of 379 merchants was obtained. In the case of the customers' survey, the figure of two million does not specify whether it refers to client visits on each day that the fair opens or during both days.

In order to validate it, the Google Earth tool was used to calculate the area of the fair. Assumptions were made about the density ofpeople that fit in a square meter, as well as about the space occupied by the fair booths.

Figure 6 shows the extension of the Barrio Lindo fair. According to the measurement tool, the fair has a perimeter of 2,931.01 m and an area of 497,399.48 m2. If it is assumed that the merchant booths have dimensions of 3 x 3 m, totaling 9 m2 per booth, the booths would occupy around 198,000 m2.

Discounting the area that the booths occupy, the area of 299,399.48 m2 would represent people's circulation spaces. Ifone square meter can be occupied by 3 or 4 people, the number of customers visiting the fair would be between 898,198 and 1,197,598 people. The first number could be related to visits on Wednesdays, when a lower density of people is expected at the fair because it is a weekday. The second could be associated with visits on Saturdays, when there is usually a greater number ofcustomers. The sum of both estimates is close to two million (2.01), so it is reasonable to think that the figures found in the documentary review consider both days of the fair.

For all scenarios, including the one in which the number of customers is the highest (two million), the calculation tool for the sample indicates a result of385 surveys.

4.2. Activities prior to field work

Considering the size of the fair and that this study is carried out as part of the research work of the Universidad Evangélica Boliviana, the students of the Research Workshop II subject collaborated as pollsters at the fair. It is important to note that the aforementioned subject precisely has the purpose of helping students understand the elements of research following the scientific method, so carrying out field work represents practical learning for the students' own research work.

The final versions of the questionnaires were shared to the students one week before the date chosen to carry out the field work. The purpose ofthe research and each question on the questionnaires were explained to them.

In the week prior to the field work, the students were trained, emphasizing the purpose of the research, how to fill out the questionnaires, what to do if the respondents do not wish to carry out the survey and the ethical aspects ofthe surveys and its fulfillment.

The logistical aspects prior to field work consisted of randomly assigning interviewers to each type of questionnaire, as well as their interviewer code. The meeting point, time, uniform and the need to have a cell phone with sufficient battery and mobile data to carry out the survey were also specified. The guide prepared with the methodological and logistical recommendations is available upon request.

4.3. Field work

Field work was carried out Wednesday, October 4, 2023 with 18 students. The work began at eight in the morning with a review ofthe characteristics ofthe survey, the ethical, technical and logistical aspects to carry it out.

During the field work, 389 responses were obtained in the group of merchants and 319 in the group of customers. Students' queries were answered through chat and costumers and merchants' responses were monitored online.

The main obstacles that the pollsters faced were related to a lower willingness to answer on the part of the costumers, who refused to answer mainly due to time reasons, since they were either circulating at the fair and did not want to stop. In the case ofmerchants, some rejections were due to sensitivity about the purpose of the survey, despite the explanations provided by the students.

4.4. Results

4.4.1. Customers

The rejections that some pollsters had were reflected in a smaller number of questionnaires answered compared to the calculated sample (319 vs. 385), which increases the margin of error of the survey from 5% to 5.49%. This value is within reasonable margins of error for the chosen confidence level though.

A first aspect that stands out about the customers' profile is that they are young, 36% are between 21 and 30 years old. Just over half of the fair's customers have an employment relationship with employers, while the rest are independent workers. 82.5% of customers declared monthly income less than or equal to Bs. 5,000 (around US$ 717), of which 55% have monthly income ofup to Bs. 2,500 (around US$ 359). The majority ofcustomers have a bachelor degree (58%) and their purchases are concentrated in clothing (60%).

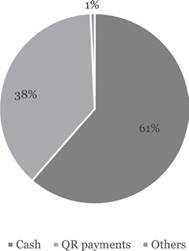

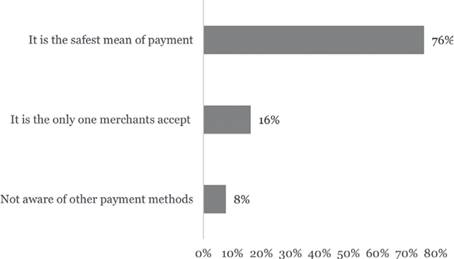

QR payments are made by 37.9% of customers, while the majority (61.4%) pays in cash (Figure 7). The main reason why customers prefer cash is because they consider it safer (76%) and, to a lesser extent, because some merchants still receive payments exclusively in cash (16.3%). Only 7.7% of customers are unaware ofalternative payment instruments to cash (Figure 8).

Note: Other refers to electronic cards.

Source: Customers' survey at the Barrio Lindo fair.

Figure 7: Payment instrument used by customers at the Barrio Lindo fair

Source: Customers' survey at the Barrio Lindo fair.

Figure 8: Reasons for cash preference among customers

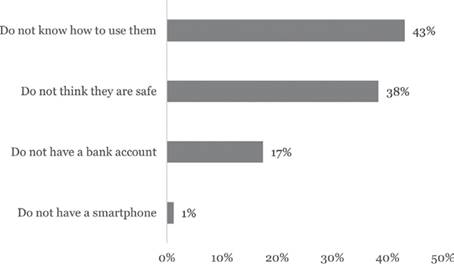

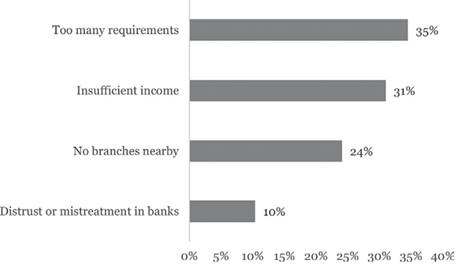

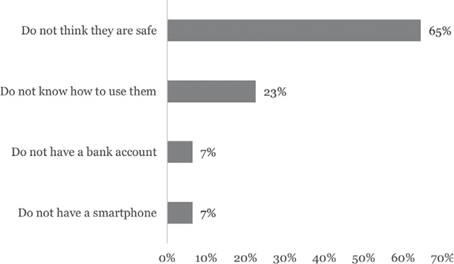

Customers who prefer cash payments are aware of immediate QR payments, but do not use them mainly because they think they are not safe or do not know how to use them (81%, Figure 9). 17% ofthe fair's customers do not have a bank account and the main reasons for this situation are related to the fact that banks ask for many requirements and, secondly, because they do not have enough income to have a bank account (Figure 10). This aspect is consistent with their income level, less than Bs. 2,500 (46% ofcustomers) and very close to the national minimum wage of Bolivia (Bs. 2,362, around US$ 339). It is also important the perception that the absence ofnearby banking agencies limits having a bank account.

Source: Customers' survey at the Barrio Lindo fair.

Figure 9: Reasons why cash customers don't use QR payments

Source: Customers' survey at the Barrio Lindo fair.

Figure 10: Reasons why customers who pay in cash do not have a bank account

Fair customers who pay with QR codes have been using them for more than a year, a behavior that is related to the significant increase in these payments as described in Section 2. A small percentage (8.3%) of customers are using these payments less than a month ago. Customers use QR payments at least once a week (70%).

The results related to customers’ banking usage seem important. Half of customers who use QR immediate payments indicate that they opened a bank account for this purpose. This suggests a one-time increase of around 169,000 new accounts in the banking system considering the more modest number ofvisitors to the fair. The estimated figure represents around 20% of the increase observed in the number of deposit accounts reported by the supervisory authority in its monthly statistical report (Autoridad de Supervisión del Sistema Financiero, 2023).

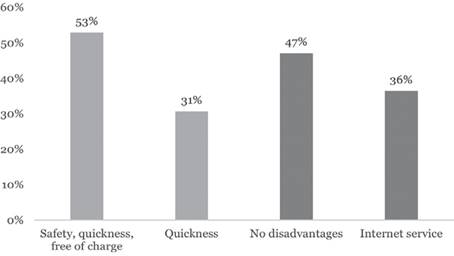

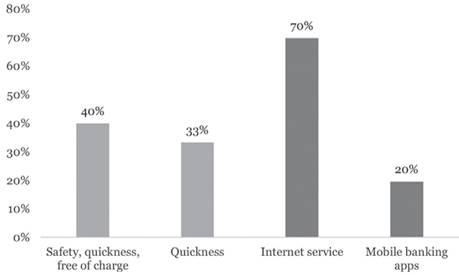

Customers identify the main joint advantage of QR payments as their quickness, safety and that no cost is associated with its use; as a standalone feature, the surveys highlighted how quickly they can make payments. Regarding the disadvantages, almost halfpoint out that QR immediate payments do not present any disadvantages and, to a lesser extent, 36.4% think that the internet service is slow or interrupted (Figure 11). 16.5% indicate problems with their mobile banking applications as a disadvantage.

Source: Customers' survey at the Barrio Lindo fair.

Figure 11: Main advantages and disadvantages of making QR payments for customers

4.4.2. Merchants

The majority of the merchants at the fair are business owners and 70% are women, whose age is between 21 and 30 years old. The percentage of merchants who declared themselves independent (56%) is consistent with the ownership they indicate over the stands (53%). They mainly offer clothing.

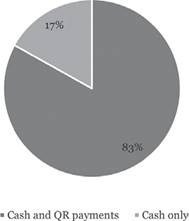

83% ofmerchants indicate that they accept cash and QR payments, while only17% accept exclusively cash (Figure 12). This group are aware of other means ofpayment, the best known being QR immediate payments. However, they do not use them because they are not safe (Figure 13). Some merchants indicated that the transfer takes time to be confirmed, which generates uncertainty feelings.

Source: Merchants' survey at the Barrio Lindo fair.

Figure 12: Payment methods that merchants offer to their customers

Source: Merchants' survey at the Barrio Lindo fair.

Figure 13: Reasons why merchants don't use QR payments

A second explanation that merchants provided for not charging with QR in their establishments is that they do not know how to use them (23%). Therefore, the need for training merchants was identified. They responded affirmatively to the possibility of training in the use ofalternative cash instruments either on a personalized basis or by joining a training group.

Merchants that offer QR payments have been using them for more than a year in 48.5% of cases. This is consistent with the increase figures in QR payments that were shown in previous sections. 43% of merchants indicate that they have used QR payments for at least three to six months, which indicates that this way of making electronic transfers has been present a relatively long time among merchants (Figure 14). An interesting fact is that 75.3% of merchants had a bank account to offer QR payments, while the remaining percentage opened one to be able to offer this alternative (Figure 15).

Source: Merchants' survey at the Barrio Lindo fair.

Figure 14: Estimated time using QR payments among merchants

Source: Merchants' survey at the Barrio Lindo fair.

Figure 15: Merchants who already had or opened a bank account to offer QR payments

76% of merchants received QR payments at least once a week, which shows a fairly frequent use of this payment alternative, especially considering that the fair is only open twice a week.

Merchants identified the main joint advantage of QR payments as safety, quickness and that they have no cost (40%). To a lesser extent, 33% specifically value quickness of QR payments as one of its advantages. The main disadvantage for merchants is the service of internet providers, whether due to aspects of speed or interruptions in service. 20% of merchants consider that processing times and/or failures of mobile banking applications represent a disadvantage for QR payments (Figure 16).

Source: Merchants' survey at the Barrio Lindo fair.

Figure 16: Main advantages and disadvantages of making QR payments for merchants

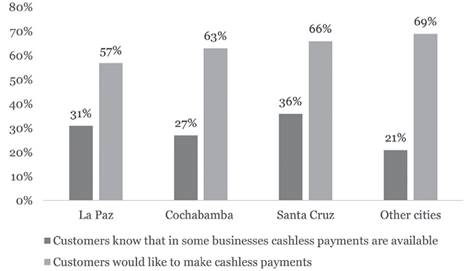

Finally, 55% of merchants at the fair think that their sales increased due to the availability of QR payments. Ofthat percentage, 77% consider that their sales increased by up to 10% due to having the QR payment option available (Figure 17).

5. Conclusion

Electronic payments have spread significantly in recent years in the world and in Bolivia as well. A peculiar aspect in this case is its use in informal sectors of the economy. For this reason, the Barrio Lindo fair in Santa Cruz de la Sierra was chosen to analyze the use of QR immediate payments and whether they could have had a positive impact on the banking usage ofcustomers or merchants at the fair.

The research mainly resorted to documentary means to obtain basic information about the fair, since it was not possible to interview its leaders. This aspect may be related to the usual susceptibility ofthe informal sector to queries related to its income-generating activities.

Customers at the Barrio Lindo fair who make QR payments represent around 38% of the total and have been doing so for more than a year, with a frequency ofat least once a week. The main joint advantage they find with QR payments is their quickness, safety and that they have no cost. Almost half of customers say they do not find any disadvantages in QR payments.

Cash, however, is the most used means of payment by customers. In part, this is because customers perceive that merchants consolidate this practice by requesting their payments exclusively in cash.

More than 80% of merchants offer QR and cash payments at the fair. Those who still continue to collect cash only think that QR payments are not safe or do not know how to use them. Like customers, most merchants have been using QR payments for more than a year, with a frequency of at least once a week. Merchants also consider that the safety, quickness and no cost features are the main advantages of making their payments with QR codes, while interruptions or lower speed of the service of internet providers would be their main disadvantages.

The majority of merchants perceive that their sales increased by offering QR payments. The increase in sales was estimated at up to 10% in 77% of the cases.

Regarding banking usage, half of customers indicate having opened a bank account in order to use QR immediate payments, which represents an estimated number of169,000 new bank accounts (for once). On the other hand, most merchants began to offer QR payments having a bank account and only 25% opened one to access QR payments. The results, mainly on costumers' side, reflect a positive impact on banking access, since opening a bank account can have benefits in the future such as access to credit and other banking services. An additional result that is important to highlight is that the possibility of offering QR payments to customers favored the sales ofthe fair's merchants.

The fact that both customers and merchants who do not use immediate payments with QR perceive them as unsafe or do not know how to use them, opens an opportunity to train these people either through initiatives organized by banks or by educational institutions in alliance with financial entities. Likewise, there is a need for telecommunications authorities to evaluate the quality of the internet service that users receive in general, since this aspect has been highlighted as a disadvantage associated with the use ofQR immediate payments.

Finally, there is a field of research to continue inquiring the use of QR payments in other informal spaces, such as in small and micro businesses and in other informal activities where payments have smaller valúes as would be expected at neighborhood markets with basic retail products such as meat, fruits and vegetables.