1. INTRODUCTION

Mental health is defined as the ability to realize one’s potential, manage life’s stresses, learn effectively, and work productively. It is a vital aspect of well-being that enables individuals to build relationships and make informed personal and social decisions [1]. Consequently, mental health disorders are widely recognized as a significant issue in many countries, marked by clinically notable disturbances in cognition, emotional regulation, or behavior (ibid). Particularly in the workplace, mental health conditions pose a threat to firms’ profitability. Disorders such as anxiety and depression, along with symptoms like fatigue, insomnia, headaches, and high blood pressure, can escalate to severe physical and mental health issues, usually linked in productivity losses [2].

One of the main contributors to these productivity losses is Absenteeism. It occurs when employees fail to appear at their workplace, with or without prior notification. It is a multifaceted issue with significant personal, social, and economic repercussions, causing numerous unproductive actions among employees and imposing substantial costs on organizations [3]. These costs encompass productivity losses, overtime expenses, training and temporary replacement expenses, and costs related to employee turnover [4]. In the United States, the economic burden of mental illnesses associated with Absenteeism has increased over the years, and it is projected to result in $7.4 billion during 2024 [5].

Another significant factor affecting productivity is Presenteeism. It occurs when employees come to work despite poor medical conditions, leading to decreased productivity and impaired performance. This can be due to various health issues, ranging from minor to serious illnesses, as well as factors like job satisfaction, worker morale, job design, individual motivation, as factors like job satisfaction, worker morale, job design, individual motivation, a sense of worth, job training, and the workplace environment and culture [6]. Presenteeism measures the reduction in productivity among employees whose health problems have not necessarily caused Absenteeism, making its identification challenging, and its costs can exceed those of Absenteeism [4]. Indeed, [5] Presenteeism costs are anticipated to reach around $45.7 billion in 2024 (almost six times the economic burden of Absenteeism).

Moreover, in the context of Latin America and the Caribbean, mental health challenges are exacerbated by deficiencies in public health systems, limited social protection, low-income levels, and scarce medical resources [7]. Compounding this, countries in the region allocate fewer resources to mental health care compared to other regions with similar income levels [8]. This underinvestment contributes to the development of severe conditions, such as burnout syndrome, characterized by profound mental exhaustion [7]. Burnout not only hinders individuals' ability to perform their tasks effectively but also increases presenteeism, amplifying productivity losses in workplaces [9]. These regional challenges illustrate the broader implications of inadequate mental health care on labor productivity and emphasize the importance of integrating perspectives from Latin America and the Caribbean into the global conversation on workplace mental health.

Despite a consensus in the literature that both absenteeism and presenteeism are major impacts of mental health disorders on economic activity [10], studies identifying the risk and mitigating factors of these issues remain varied and sparse. While this paper primarily aims to determine the underlying drivers and deterrents of absenteeism and presenteeism among individuals with mental illnesses, with a focus on workplace factors drawn from data on U.S. tech employees, the discussion of Latin America and the Caribbean highlights the importance of tailoring workplace mental health interventions to specific economic, cultural, and structural contexts. By exploring drivers and deterrents of absenteeism and presenteeism in diverse regions, future studies can inform more inclusive strategies that address mental health challenges on a global scale.

For this purpose, cross-sectional data from United States tech employees is utilized, extracted from the Open Sourcing Mental Health in Tech Survey (OSMI Survey) during the period 2017-2022. The tech sector is considered in this study because it encompasses 20% of US private employment and contributes almost 10% of the country’s GDP, making it one of the most important segments of the economy [11].

The study reveals that a personal or family history of mental health disorders significantly increases Absenteeism and Presenteeism in the workplace, negatively impacting productivity. Additionally, personal stigma around mental health is a key driver of Absenteeism. These findings emphasize the importance of addressing mental health and stigma to improve workplace well-being and performance.

Thus, the structure of this study will be as follows: Section Two will consist of a literature review on the main drivers of Absenteeism and Presenteeism identified by previous authors. Section Three will explain the data treatment process followed by the author and provide descriptive statistics for the relevant variables considered. Section Four will describe the model, and the econometric technique used for estimation. Section Five will present the results obtained and discuss the estimated parameters. Finally, Section Six will offer a conclusion for the study.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

In this regard, the relevance of absenteeism and presenteeism to the economy is critical. Specifically, business productivity, through reduced employee performance and organizational costs, is consistently affected by both effects. For instance, as Johns [12] concludes, in addition to impacting individual productivity, presenteeism also reduces work quality even under optimal conditions. Similarly, excessive absenteeism negatively affects team morale, creating coordination issues and a decrease in overall efficiency [13].

2.1 Absenteeism

Several studies have found risk and mitigating factors of Absenteeism among employees with mental health disorders. [14] made a scoping review of prognostic factors of sickness absence due to mental illnesses, finding the following potential drivers and deterrents:

Past History of Mental Health Disorders: Recurring mental illnesses can strongly predict reduced functioning or difficulty adjusting to work, which can result in increased Absenteeism. Similarly, individuals with mental disorders may learn to request sick leave after successive episodes, and doctors may be more inclined to approve sick leave in cases where previous episodes have occurred [15]. Hence, a positive relationship between history of past mental disorders and Absenteeism can be inferred.

Openness with Employer: A supportive and open workplace environment, where individuals feel comfortable disclosing their mental health challenges, can reduce Absenteeism. [16] found a negative relation between supportive behavior in workplaces and Absenteeism. Nonetheless, the willingness to openly talk about their mental issues with their employers without any negative consequences was found to be less prevalent in women than in men [17]. In contrast, [18] did not find statistically significant causal effects; they only found negative correlations.

Openness with Co-Workers: Low social support contributes to poorer mental health and lower work ability, increasing absenteeism by periods of time longer than six weeks [19]. Nonetheless, it was found that discussions about mental health with co-workers increased during the pandemic, helping reduce absenteeism in some cases [17].

Family History of Mental Health Disorders: Individuals with a family history of mental illnesses (e.g. depression) are more likely to inherit genetic predispositions that make them susceptible to episodes of these disorders [20]. Moreover, growing up in an environment where mental issues are prevalent can lead to the development of maladaptive coping mechanisms and stress responses, increasing Absenteeism [18]. Nonetheless, there is not empirical consistent evidence that supports this theoretical relation.

Gender: Differences in gender roles, responsibilities, and stress responses may theoretically contribute to variations in Absenteeism rates. However, the impact can be either negative or positive. On the one hand, women may experience unique stressors from balancing work and family du- ties, potentially leading to higher Absenteeism. This positive relationship has been observed by [21] and [22]. On the other hand, some authors suggest that women are more likely than men to recognize nonspecific feelings of psychiatric symptoms as conscious problems, making them more likely to seek professional help early, which can prevent sickness absence [23];[24]

Firm Size: The size of a company can influences Absenteeism in various ways. On one hand, workers in large firms are often part of extensive internal networks, which can enhance collaboration but also increase the potential for contagion, leading to more absence requests and greater pressure on employers to grant leave [25]. On the other hand, large companies have the resources to implement comprehensive wellness, mental health, and leave programs, which can help reduce health-related Absenteeism. Therefore, the overall effect is ambiguous.

Personal Stigma: Individuals who internalize stigmatic beliefs may be less likely to disclose their mental health issues and seek appropriate treatment, fearing that taking time off for mental health reasons might lead to being perceived as weak or unreliable [26]. In contrast, anticipated stigma, which refers to the fear that others will discriminate against or judge someone with a mental illness, was positively correlated with Absenteeism (ibid.). This indicates that while personal stigma may drive individuals to remain at work despite health issues, anticipated stigma might cause them to take sick leave to avoid potential discrimination. Thus, the overall effect of stigma on Absenteeism is complex, with personal stigma potentially reducing Absenteeism, while anticipated stigma may increase it.

Medical Coverage: The lack of medical coverage increases the likelihood of untreated mental health issues, contributing to Absenteeism. Nonetheless, most of the incidence associated with this “lack” may be due to ignorance about the available mental health programs covered by health insurances [27].

2.2 Presenteeism

Unlike Absenteeism, Presenteeism often remains underreported and less visible, despite its profound organizational and personal implications. A growing body of literature has explored various factors that contribute to this phenomenon, highlighting the interplay between individual characteristics, workplace environments, and societal attitudes. Below, key factors influencing Presenteeism in individuals with mental health disorders are examined, drawing on evidence from multiple sources:

Family History of Mental Health Disorders: Individuals with a family history of mental disorders may be more likely to internalize stigma and feel pressure to conceal their own mental health struggles, leading them to attend work while unwell. Additionally, the added stress and burden of managing both one’s own mental illness and supporting family members with mental health issues can exacerbate symptoms and further contribute to Presenteeism [28];[29].

Past History of Mental Health Disorders: Past psychiatric history was significantly correlated with greater perceived job stress, which in turn predicted higher levels of productivity loss and Presenteeism at work [30]. Similarly, Presenteeism itself can be a risk factor for developing depression, suggesting a cyclical relationship between past mental illness and ongoing Presenteeism [31].

Age: A study found that younger age was significantly correlated with higher levels of Presenteeism. This may be caused younger workers feeling more pressure to prove themselves or fearing job loss if they take time off for mental health reasons [28]. In contrast, another study showed that older age was a significant predictor of neuroticism, a personality trait linked to greater vulnerability to mental disorders and Presenteeism. This indicates that age may increase Presenteeism risk through its association with neuroticism [31]. So, the overall effect is ambiguous.

Openness with employer: When employees feel supported and able to address their mental health needs without stigma or fear, they are more likely to maintain higher levels of productivity and engagement at work, ultimately benefiting both individuals and the organization, reducing Presenteeism. [16] found that workplaces demonstrating supportive behaviors, such as encouraging open dialogue about mental health, providing resources for mental well-being, and offering flexible work options, experience lower levels of Presenteeism.

Openness with family: This factor may present some ambiguity because, on one hand, understanding and support from family members can mitigate feelings of isolation or stigma associated with mental disorders, thereby enabling individuals to manage their conditions more effectively and maintain consistent productivity in the workplace. Conversely, when family responsibilities become overwhelming, some individuals might turn to work as a form of escape, resulting in Presenteeism, which can adversely affect productivity [32]. Furthermore, the interference of work with family life has been associated with lower perceived work performance, further contributing to Presenteeism. [33].

3. DATA

3.1 Data Treatment

The data utilized in this study was collected from surveys created by Open Sourcing Mental Illnesses (OSMI), a non-profit organization focused on promoting mental health awareness, education, and resources within the tech industry. Specifically, the surveys examined were from the 2017-2022 period.

The sample selection methodology followed the data treatment approach outlined by Rasheed [34]. As a result, all variables used by the authors in their database construction were maintained. However, some additional variables from the surveys, which were not previously considered, were included. Table 1 lists all the variables used in this paper, with intermediate variables being those used during data cleaning and principal variables being those used for estimation purposes.

Only responses from U.S. employees were utilized, since. Self-employed individuals and employees with roles not related to the tech sector were not included in the analysis. Additionally, some other corrections were made ([34] for more details), Tabla 1.

TABLE 1 - DESCRIPTION OF VARIABLES CONTAINED IN THE DATASET

| Variable Name | Description | Type of Variable |

|---|---|---|

| Self Employed | Are you self-employed? | Intermediate |

| Tech Company | Is your employer primarily a tech company/organization? | Principal |

| Tech Related Role | Is your primary role within your company related to tech/IT? | Intermediate |

| Workplace Resources | Does your employer offer resources to learn more about mental health disorders and options for seeking help? | Principal |

| Employer Discussion | Have you ever discussed your mental health with your employer? | Principal |

| Co-Worker Discussion | Have you ever discussed your mental health with coworkers? | Principal |

| Medical Coverage | Do you have medical coverage (private insurance or state-provided) that includes treatment of mental health disorders? | Principal |

| Openness with Family | How willing would you be to share with friends and family that you have a mental illness? | Principal |

| Age | What is your age? | Principal |

| Gender | What is your gender? | Principal |

| Country | What country do you live in? | Intermediate |

| Absenteeism | If a mental health issue prompted you to request a medical leave from work, how easy or difficult would it be to ask for that leave? | Principal |

| Presenteeism (Non-Treated) | If you have a mental health disorder, how often do you feel that it interferes with your work when not being treated effectively (i.e., when you are experiencing symptoms)? | Principal |

| Presenteeism (Treated) | If you have a mental health disorder, how often do you feel that it interferes with your work when being treated effectively? | Principal |

| Employer Score (Mental Health) | Overall, how much importance does your employer place on mental health? | Principal |

| Physical-Mental Health Preferences | Would you feel more comfortable talking to your coworkers about your physical health or your mental health? | Principal |

| Family History | Do you have a family history of mental illness? | Principal |

| Mental Health (Past) | Have you had a mental health disorder in the past? | Principal |

Gender: Responses related to the "Male" and "Female" gender were standardized, while the other responses were cataloged as "Other".

Medical Coverage: All people who reported that their employers provide mental health services as part of their health insurance were categorized as having mental health coverage. In the same way, all responses of "not applicable for coverage" were assigned to the category "No".

Age: Values greater than 75 were replaced with the mean. This adjustment was made considering the life expectancy in the United States and was necessary because individuals reporting ages over 75 provided values exceeding 120 years, which were clearly wrong. However, after narrowing the sample to include only U.S. tech employees, only one replacement was required in the sample of interest. Since the primary goal of the study was to preserve sample size, simple mean substitution was selected as the most appropriate approach.

Dummy Variables: Labelled as "TRUE" (if value=1.0) or "FALSE” (if value = 0.0).

Firm Size: Minor corrections were made to the values of the variable. "25-Jun" (25-6) and "5-Jan" (5-1) values were assigned to the categories (6-25) and (1-5) respectively.

Additional corrections: For the variables of Absenteeism, past (own and family) history of mental health disorders, medical coverage, workplace resources, and Presenteeism, uncertain values classified as "I don’t know", "Maybe", "Possibly", "Not applicable" were treated as missing values. The treatment was necessary since those phrases can simultaneously denote uncertainty, hesitation, avoidance, or even an intentional deflection of responsibility when addressing issues related to mental health, workplace environment, and personal productivity. This type of answers reflects the vagueness and flexibility inherent to pragmatic ambivalence, allowing individuals to answer without committing to a single, definitive position, such that responses depend on context and cognitive relevance [35]. Particularly, in psychotherapy, ambivalent answers may also arise from conflicting mental states where individuals may simultaneously lean toward and away from a decision or viewpoint, such that the mental health trajectory of individuals may be represented in their responses as an indirect indicator [36]. Nonetheless, the “true” state behind that ambivalence is a latent variable, which may require to be imputed based on patterns observed in the data available (related to the individual context).

After making those adjustments, an analysis about the rate of missing values of each variable was made to determinate if they were significant and randomly distributed. Ideally, it is expected that missingness do not depend to both observed and unobserved data, since in those cases incomplete records are said to be Missing Completely at Random (MCAR), and techniques of listwise deletion (when data analysis excludes completely the cases with missing data), or mean substitution can be applied [37]. Nonetheless, data shows that all variables seem to have more than 5% of the observations as missing data, so excluding those individuals may significantly reduce the sample size and the precision of estimates. Additionally, since ambivalent behavior was detected in some responses in various variables, and the information of interest for the analysis is related to the latent true behavior behind the ambivalence, some part of missing data was systematically generated according to the observed answers provided, so the MCAR assumption does not hold, and excluding those persons from the analysis, or simply applying a mean substitution, may introduce selection bias to estimations by disproportionately affecting participants likely facing mental health issues.

TABLE 2 - RATE OF MISSING VALUES PER VARIABLE

| Variable | Missing | Percent Missing |

|---|---|---|

| Tech Company | 53 | 6.59% |

| Employer Discussion | 97 | 12.06% |

| Co-Workers Discussion | 55 | 6.84% |

| Medical Coverage | 188 | 23.38% |

| Openness with Family Score | 97 | 12.06% |

| Reaction Score | 103 | 12.81% |

| Tech Sector Score | 147 | 18.28% |

| Race | 22 | 2.74% |

| Workplace Resources | 225 | 27.99% |

| Family History | 199 | 24.75% |

| Absenteeism | 159 | 19.78% |

| Presenteeism (Treated) | 265 | 32.96% |

| Presenteeism (Non Treated) | 231 | 28.73% |

| Mental Health (Past) | 194 | 24.13% |

| Mental Health | 211 | 26.24% |

| Unsupportive Response Experienced | 219 | 27.24% |

| Supportive Response Experienced | 212 | 26.37% |

| Third-Person Experiences | 270 | 33.58% |

Nonetheless, literature shows that ambivalent behavior is associated to poor mental health outcomes and is considered as an easily detectable aspect of the therapeutic process [36], so the probability of its presence (which is traduced in a missing value assignation) should be determined by other factors of the individual´s context (age, workplace environments, etc.), such that the latent “true” state behind the variable can be recovered. So, since missing data may be explained with observed data, it is said to accomplish the missing at random (MAR) assumption ([37],[38]). Therefore, since MAR assumption holds, a multiple imputation based on chained equations (MICE) model was proposed to estimate the uncertain values of data. Ordinal variables were modeled by an Ordered Logit technique, while dichotomous variables were estimated by a predictive mean matching approach (considering the 2 nearest neighbors).

The number of imputations was determined by using the methodology proposed by Von Hippel [26]. Firstly, a pilot test was run considering 20 imputations (considering all the variables of table 2 for the regressions). Secondly, the principal models of this study (concerning Absenteeism and Presenteeism frequencies) were estimated. Finally, the fraction of missing information about the estimated parameters (FMI) was calculated and the number of imputations were calculated following the rule:

Where CV (se) is a coefficient of variation interpreted as the percentage by which we would be willing to see the SE estimate change if the data were imputed again. In this case, a maximum change of 5% was allowed, and it was found that 199 more imputations were needed to achieve the conditions imposed previously. So, the total number of imputations used in this study was 219, and the final number of observations was 804.

3.2 Descriptive Statistics

Table 3 shows some demographic statistics about the U.S. tech workers surveyed by OSMI organization. According to the data, 59.95% of people are male, with a mean age of 36 years, while the 34.83% are women with an average age of 34 years. The other 5.22% are identified with other genders, having a mean age of 35 years. The overall sample has an average age of 36 years with an standard deviation of 8.67 years.

TABLE 3 - SUMMARY STATISTICS OF WORKERS’ AGE BY GENDER

| Gender | Mean | Std. Dev. | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 34.22 | 8.56 | 34.83 |

| Male | 36.33 | 8.55 | 59.95 |

| Other | 34.90 | 9.70 | 5.22 |

| Total | 35.52 | 8.67 | 100 |

Concerning workplace environment data, Table 4 highlights several key points (reporting data obtained prior to the imputation process, during the pilot imputation, and after the final imputation).

TABLE 4 - EMPLOYEES’ WORKPLACE ENVIRONMENTS STATISTICS

| Variable | Imputation | N | No | Yes | Standard Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tech Company | m=0 | 751 | 25.97 % | 74.03% | 0.0160 |

| m=20 | 804 | 25.94 % | 74.06% | 0.0160 | |

| m=219 | 804 | 25.94% | 74.06 % | 0.0159 | |

| Workplace Resources | m=0 | 579 | 47.67 % | 52.33 % | 0.0207 |

| m=20 | 804 | 47.89 % | 52.11 % | 0.0199 | |

| m=219 | 804 | 48.22% | 51.78% | 0.0201 | |

| Medical Coverage | m=0 | 616 | 9.90 % | 90.10% | 0.0120 |

| m=20 | 804 | 11.54 % | 88.46% | 0.0132 | |

| m=219 | 804 | 11.48% | 88.52 % | 0.0132 | |

| Employer Discussion | m=0 | 707 | 67.04 % | 32.96 % | 0.0177 |

| m=20 | 804 | 67.05% | 32.95% | 0.0177 | |

| m=219 | 804 | 67.03% | 32.97 % | 0.0175 | |

| Co-worker Discussion | m=0 | 749 | 54.87 % | 45.13 % | 0.0182 |

| m=20 | 804 | 54.96% | 45.04 % | 0.0182 | |

| m=219 | 804 | 54.93 % | 45.06 % | 0.0180 |

Firstly, 73-74% of employees work in a tech firm, while the remaining occupy tech roles in other sec- tors. When it comes to mental health resources, only 52-53% of individuals are employed by firms that offer resources to learn about mental disorders. Additionally, 88-90% of workers have access to public or private healthcare coverage, with all these services offering treatment for mental illnesses. In terms of openness at the workplace, only 33% of employees are willing to discuss their mental health issues with their employers, and only 44-46% are open to discussing these issues with their co-workers.

Regarding the general encouragement of mental health, Table 5 presents descriptive statistics on various perception scores provided by the respondents. Employers were rated an average of 5.29 out of 10 for their attention to mental health issues, while co-workers received a slightly higher average of 5.52 out of 10. In the overall tech sector, perceived support for employees with mental illnesses was rated at 2.6 out of 5. These results indicate a moderate level of concern in workplace environments for supporting individuals with mental disorders. However, the willingness of individuals to discuss their mental condition with family and friends is relatively high, with a score of 7.19 out of 10.

TABLE 5 - DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS OF SCORE VARIABLES

| Variable | Imputation | N | Mean | Mean Standard Error | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Openness with Family | m=0 | 707 | 6.6322 | 0.1018 | 0 | 10 |

| m=20 | 804 | 6.6374 | 0.0976 | 0 | 10 | |

| m=219 | 804 | 6.6329 | 0.1001 | 0 | 10 | |

| Tech Sector Score | m=0 | 657 | 2.5860 | 0.0353 | 1 | 5 |

| m=20 | 804 | 2.5852 | 0.0381 | 1 | 5 | |

| m=219 | 804 | 2.5865 | 0.0358 | 1 | 5 | |

| Workplace Reaction Score | m=0 | 701 | 5.4137 | 0.0843 | 0 | 10 |

| m=20 | 804 | 5.4110 | 0.0818 | 0 | 10 | |

| m=219 | 804 | 5.4100 | 0.0832 | 0 | 10 | |

| Employer Score (Mental Health) | All | 804 | 5.1256 | 0.0875 | 0 | 10 |

When examining personal experiences with mental health, Table 6 shows that 64-65% of respondents have had mental disorders in the past, and 67% have a family history of mental illnesses. Therefore, the majority of individuals have been exposed to the consequences of mental health issues.

TABLE 6 - EMPLOYEES’ EXPERIENCE WITH MENTAL HEALTH DISORDERS

| Variable | Imputation | N | No | Yes | Standard Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental Health (Past) | m=0 | 610 | 34.92% | 65.08% | 0.0193 |

| m=20 | 804 | 34.83% | 65.17% | 0.0184 | |

| m=219 | 804 | 34.99% | 65.01% | 0.0182 | |

| Family History | m=0 | 605 | 32.56% | 67.44% | 0.0191 |

| m=20 | 804 | 32.62 % | 67.38% | 0.0185 | |

| m=219 | 804 | 32.43% | 67.57 % | 0.0183 |

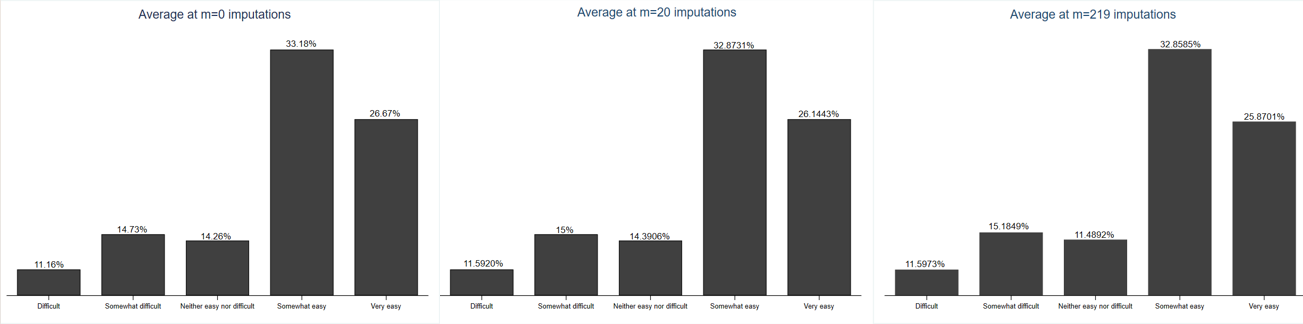

With respect to the paper’s outcome variables, Figure 1 shows the distribution of U.S. employees according to the ease of obtaining authorized Absenteeism due to mental health disorders. In general, employees are more likely to find it somewhat easy (32-33%) rather than somewhat difficult (14-16%) to get authorized leave, indicating that Authorized Absenteeism is relatively common among U.S. tech employees.

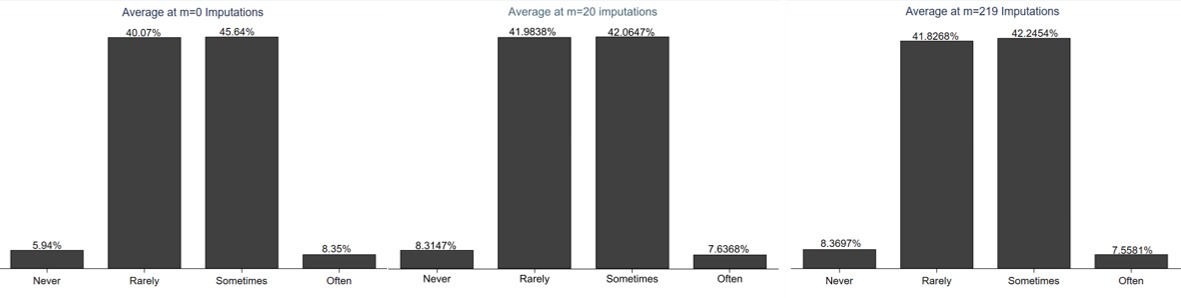

Similarly, Figure 2 shows the distribution of U.S. tech employees according to their propensity to experience Presenteeism when a mental health disorder is not properly treated. As expected, workers have more frequent episodes of productivity loss (often Presenteeism) when suffering from a mental health disorder (55-64%), while those who rarely experience Presenteeism remain between 5-10%.

Figure 2: Distribution of U.S. Tech Employees by their Propensity to Suffer from Presenteeism (when not treated properly).

Figure 3 shows the distribution of U.S. tech employees according to their propensity to experience Presenteeism when a mental health disorder is properly treated. Contrary to the previous results, workers have less frequent episodes of productivity loss when treated, with 42-46% of respondents experiencing Presenteeism sometimes, and 40-42% rarely experiencing it.

4. MODEL SPECIFICATION

As the dependent variables in this research are ordinal measures of the degree of Absenteeism and Presenteeism among U.S. tech employees, an ordered logit model is used for the estimations. It is built on the idea of a latent (unobserved) continuous variable.

Let Y ∗ denote this latent variable, which is related to the observed ordinal variable Y. The latent variable Y ∗ can be expressed as:

where:

X = (X 1,X 2, . . .,X k ) is a vector of explanatory variables.

β is a vector of coefficients to be estimated.

ϵ is a random error term, typically assumed to follow a logistic distribution.

The observed ordinal variable Y is related to the latent variable Y ∗ through a series of thresholds or cut points, α j , such that the probability of the observed outcome Y being in category j is given by:

for j = 1, 2, . . . , J, where α0 = - ∞, α J = ∞, and Λ denotes the logistic cumulative distribution function:

The parameters of the ordered logit model, αj and β, are estimated using Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE). The log-likelihood function for a sample of n observations is:

The parameters α and β are estimated by maximizing this log-likelihood function using numerical optimization techniques. Nonetheless, the constant β0 of the latent variable in equation (1) is anchored at a value of zero to provide a scale when estimating the thresholds.

4.2 Independent and Dependent Variables

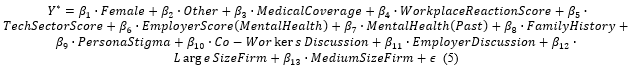

4.2.1 Absenteeism Model

To appropriately estimate episodes of absenteeism, it is important to consider several fundamental aspects that researchers identify as influential. For that reason, factors recognized in the literature review were used as the main explanatory variables. Particularly, the equation proposed for modelling the latent variable related to Absenteeism estimated is given by (5):

where:

Y=Absenteeism: Categorical variable defined from 1 (if the facility of Absenteeism is difficult) to 5 (if the facility of Absenteeism is very easy).

Female: A dummy variable that takes the value of "1" if the individual is female. Gender disparities significantly influence absenteeism. Women have shown to be more affected by mental health issues that interfere with work, possibly due to societal pressures and workplace dynamics ([24], [17]).

Other: A dummy variable that takes the value of "1" if the individual is neither male nor female. Rasheed [34] categorized these responses separately, recognizing that societal and organizational biases might affect their mental health and absenteeism patterns.

Medical Coverage: A dichotomous variable that takes the value of "1" if the individual has access to mental health services as part of their healthcare coverage. Paul & Das [27] noted that at least 65% of employees in tech sector lacked access to wellness programs or didn’t know their existence, despite many expressing a desire for treatment. That situation increases the likelihood of untreated mental health issues, directly impacting Absenteeism.

Workplace Reaction Score: A variable that measures the individual’s perception of how well their employer and co-workers would react if they knew the individual has a mental health issue (0-10).

Tech Sector Score: A variable that measures the individual’s perception of how much importance the tech sector places on mental health issues (0-10). Patel [40] showed that industries prioritizing mental health foster a culture of openness, reducing absenteeism. Conversely, sectors where mental health is undervalued may see higher absenteeism due to unmet needs for support.

Employer Score (Mental Health): A variable that measures the individual’s perception of how much importance their employer places to mental health issues (1-10). The organizational culture regarding mental health directly influences absenteeism. According to Patel [40], employers emphasizing mental health encourage treatment-seeking and reduce absenteeism. Similarly, Paul & Das [27] found that supportive employers foster open discussions, which mitigate absenteeism risks.

Mental Health (Past): A dichotomous variable that takes the value of "1" if the individual had a mental illness in the past. Having a history of mental health issues may be a strong predictor of future absenteeism. Hallsten [21] showed that individuals with a history of mental health challenges have higher risk of long-term absences. Mitravinda [17] noted that such individuals are more vulnerable to relapses, further contributing to absenteeism.

Family History: A dichotomous variable that takes the value of "1" if the individual’s family has a history of mental disorders. Family history increases vulnerability to mental health issues. Schmidt [41] highlighted the role of environmental and genetic factors in shaping mental health outcomes, while Mitravinda [17] linked family history to higher absenteeism risk due to increased vulnerability.

Personal Stigma: A dichotomous variable that takes the value of "1" if the individual prefers to talk about physical health issues rather than mental health issues. Personal stigma discourages help-seeking behaviors, leading to untreated conditions and Absenteeism [42]. Docksey [43] and Lannin [26] noted that internalized stigma reduces the likelihood of addressing mental health issues, increasing absenteeism as a coping mechanism.

Co-Workers Discussion: A dummy variable that takes the value of "1"if the individual has ever discussed about his/her mental illness with their coworkers. Workplace discussions act as informal support systems. Mitravinda [17] found that open conversations with co-workers, particularly during the pandemic, improved support and reduced absenteeism risks.

Employer Discussion: A dummy variable that takes the value of "1"if the individual has ever discussed about his/her mental illness with their employer. Communication with employers about mental health issues reflects organizational openness. Paul & Das [27] showed that supportive environments facilitate such discussions, mitigating absenteeism.

Large Size Firm: A dichotomous variable that takes the value of "1" if the individual´s firm has more than 1000 employees. Larger firms may reduce absenteeism due to their structured hierarchies and better resource management. Kensbock theorized that mental health issues are less likely to “spread” in larger organizations, while Barmby & Stephen [44] noted that such firms manage absenteeism costs effectively.

Medium Size Firm: A dichotomous variable that takes the value of "1" if individual´s firm has between 100 to 1000 employees. Similar principles apply as for large firms.

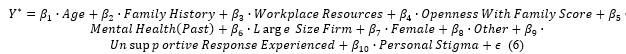

4.2.2 Presenteeism Model

The model proposed for the latent variable of Presenteeism is given by equation (6):

where:

Y=Presenteeism: Categorical variable defined from 1 (if episodes of Presenteeism when having mental disorders never occur) to 4 (if the episodes occur often).

Age: The individual’s age. Age affects productivity due to variations in physical and cognitive capacities over the life cycle. Wee [45] report a negative significant relationship between the age of the workers and their propensity towards presenteeism. Cho [46] also found a significant relationship between age and presenteeism when controlling by age discrimination, a positive relationship arose from those whose response was affirmative, however more episodes of presenteeism were found in the elder group contradicting the previous study, these clashing results opens ambiguities when regarding the causal effect of age in this phenomenon.

Family History: Patel [40] found family history and interference with work (presenteeism) as a motivating factor for seeking treatment for mental health, the latter was also found relevant by Paul & Das [27] who inferred that presenteeism is a problem at least somehow common among those interviewees who declared having a mental condition.

History of Mental Issues: Esposito [47] found that diagnosed members of the workforce tend to experience lapses of unproductivity more often than those who do not, based on the test SPS-6 from Stanford. Although the authors do not establish any causal relation, the statistical evidence proves to be significant to further explore the inclusion of past mental health issues as an extrapolation of those findings to deepen the knowledge about said connection.

Workplace Resources: A dichotomous variable that takes the value of 1 if the individual´s firm offer resources to learn about mental health issues. Mitravinda [17] emphasizes the protective role of workplace resources against presenteeism.

Openness with Family Score: A variable that measures the willingness of the employee to share his/her mental condition to family or friends (1-10). Janssens et al. [48] and Peters et al. [38] highlight the importance of family-related dimensions and social support in influencing presenteeism.

Personal Stigma: Self-stigma is associated with diminished self-esteem and poor self-efficacy, which in turn leads to the belief of not being capable of working [49].

Gender: Empirical studies suggest that there are disparities between genders when measuring sickness presenteeism via satisfaction with the supervisor, among other regressors in which disparities were less notorious ([50], [51], [52])

Unassertive Response Experienced: A dummy variable that takes the value of "1" if the individual has seen or experienced a badly handled response to a mental issue in his/her workplace. Paul & Das [27] highlight correlations between poorly handled mental health responses and presenteeism.

5. ESTIMATIONS

Before explaining the estimation results, it is important to highlight that the sample was obtained from voluntary employees who took the OSMI survey online, such that a self-selection bias component is present. Additionally, sampling weights were not available, so statistical inference for the entire population of U.S. is limited, since labor supply and demand of the tech sector, are not homogeneous in all States.

It is important to note that the analysis for both Absenteeism and Presenteeism may be subject to potential endogeneity (specially for variables related to personal stigmas and workplace environments), as unobserved factors could simultaneously influence the explanatory variables and the outcomes. Consequently, the findings should be interpreted as associations rather than definitive causal relationships.

5.1 Absenteeism Model Estimation

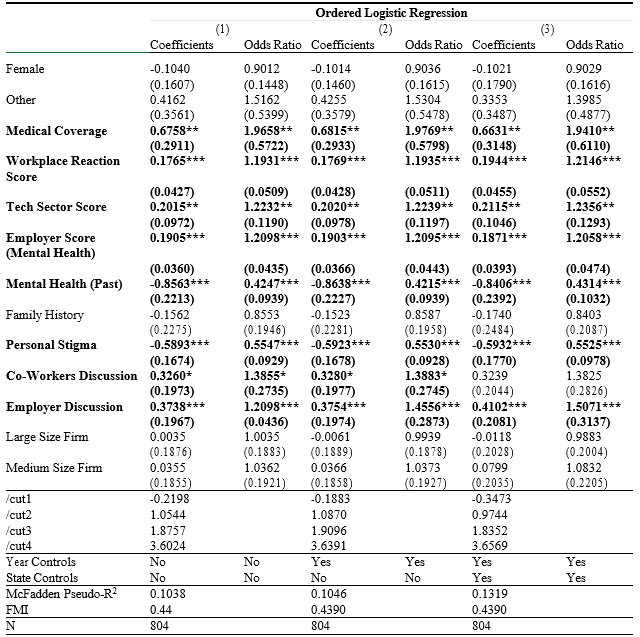

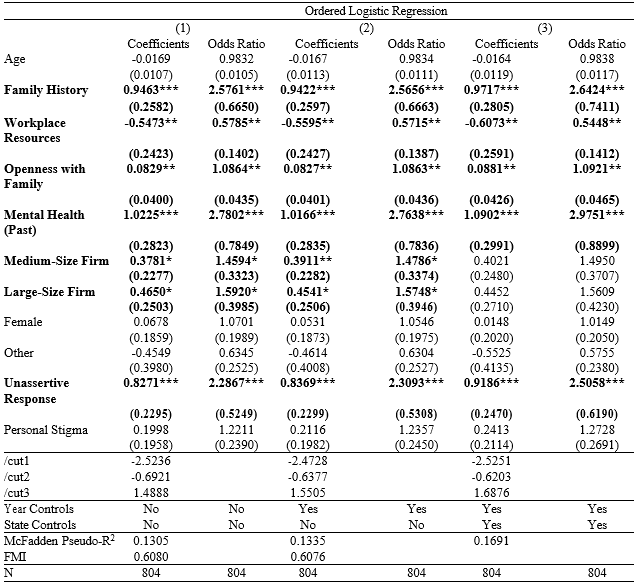

Table 8 presents the regression results for the Absenteeism model. Three different models were estimated, incorporating controls for the survey year and the respondent’s state of residence. However, prior to analyzing these results, Table 7 outlines the goodness-of-fit measures for the three ordered logit models compared to an ordered probit specification. This comparison was conducted to determine which model was more appropriate for the data.

The results suggest that, across all models, the ordered logit (ologit) specification outperforms the ordered probit (oprobit) in terms of both sensitivity (recall) and specificity. This suggests that the logistic distribution provides a better fit for the data. This finding aligns with the common preference for logit models in scenarios where data exhibit patterns emphasizing the tails of the distribution, such as variables with more extreme probabilities (as observed with absenteeism in Figure 1).

When comparing the three ologit models, the highest sensitivity and specificity were achieved in Model (3), which incorporates both survey year and state controls. Consequently, the subsequent estimation of margins will rely on Model (3), while coefficients and odds ratios for all models are provided for readers to conduct further analysis.

Despite these variations, all ologit models demonstrate sensitivity values in the range of 0.32-0.34 and specificity values around 0.83. This indicates that the regressors primarily capture structural factors that help explain why employees with mental health disorders are less likely to engage in absenteeism. This outcome is particularly significant for firms in the tech sector, where the costs of implementing well-being programs can be substantial. According to the National Safety Council and NORC at the University of Chicago [53], the costs associated with lost productivity average $4,783 annually per employee, while turnover costs average $5,733 annually per employee. Nevertheless, mental health support programs have an expected return of $4 for every dollar invested per employee. By identifying individuals at higher risk and facilitating more efficient resource allocation, the model supports the implementation of profitable, targeted interventions.

TABLE 7 - SENSIBILITY AND SPECIFICITY FOR ABSENTEEISM MODELS

| Model | Ordered Logit | Ordered Probit | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensibility | Specificity | Sensibility | Specificity | ||

| Model (1) | 0.3274 | 0.8340 | 0.3274 | 0.8340 | |

| Model (2) | 0.3289 | 0.8345 | 0.3289 | 0.8345 | |

| Model (3) | 0.3430 | 0.8378 | 0.3430 | 0.8378 | |

With the model characteristics discussed, Table 8 presents the regression estimates of the ologit specifications. It is important to highlight that all models have a Fraction of Missing Information close to 0.44, which means that 44% of the variability of the estimates is due to missing data. Nonetheless, this is acceptable under MAR assumption since it shows that the estimations do not vary significantly among all imputations, and since more than 20% of observation presented missing values in some category. This shows that the error of imputations in these models may not be particularly critical.

On the other hand, results in Table 8 indicate that key explanatory variables statistically associated with absenteeism include medical coverage, perception scores (related to workplace reactions and encouragement within the tech sector), personal stigma regarding mental health issues, past mental health disorder history, and openness with employers.

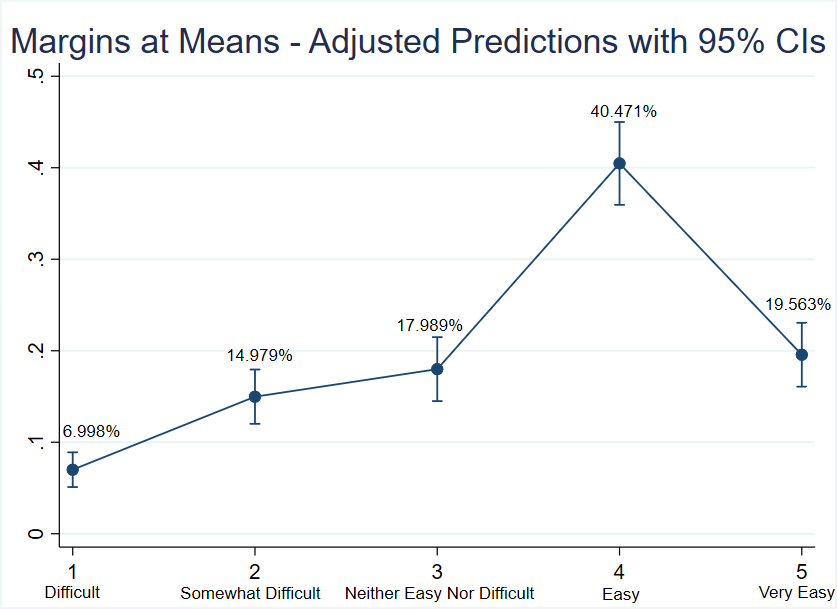

Particularly, results suggest that, based on the model, a person with an average profile-male, working in a medium-sized firm, with personal stigma related to mental illnesses, with past history of mental health issues, a family history of mental disorders, and an assigned score of 5.13 to their employer (see Section 3.2)-is estimated to have a probability of 7% of finding Absenteeism difficult, 14.98% of finding it somewhat difficult, 17.99% of finding it neither easy nor difficult, 40.47% of finding it easy, and 19.56% of finding it very easy, as shown in Figure 4.

TABLE 8 - ABSENTEEISM - ORDERED LOGIT REGRESSION RESULTS

*p<0.1; **p<0.05; ***p<0.01 Robust Standard Errors in Parentheses.

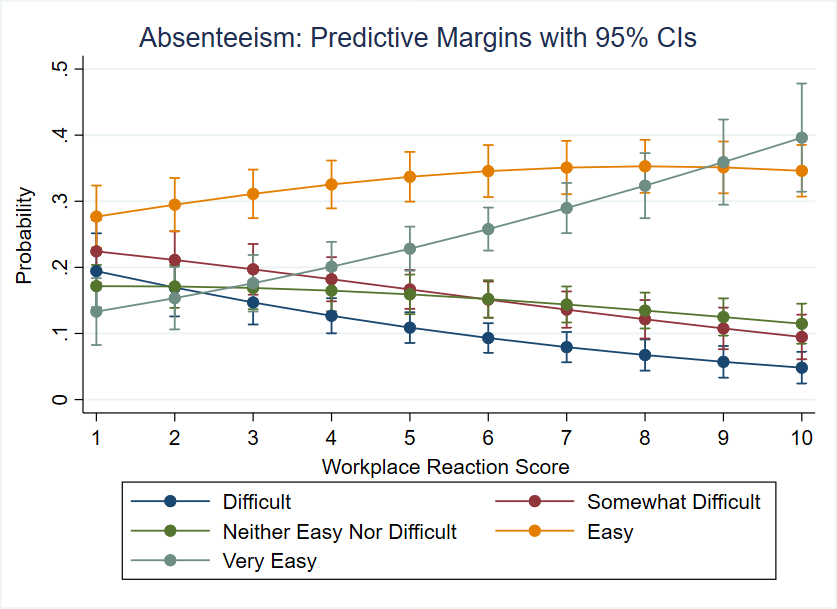

Similarly, ceteris paribus, the estimates suggest that marginal increases in the perceived workplace reaction score assigned to the employer are associated with an increased probability of higher levels of Absenteeism, thereby reducing the chances of low and moderate Absenteeism, as shown in Figure 5. Specifically, odds-ratios showed that, in average, the probability of experiencing Absenteeism "Easy" or "Very Easy" are 19% higher than experiencing it "Difficult" or "Somewhat Difficult" when the grade of positive reaction within workplace increases by one point.

Surprisingly, these results seem to contradict the relationship found by Hamberg-van Reenem [16]. However, a potential explanation is that when employees face a mental disorder, there may be an association between employers who care about mental health issues and a higher likelihood of granting absence leave to prevent potential complications and future productivity losses. This association may initially correlate with increased Absenteeism, though potentially as part of a positive and preventive approach

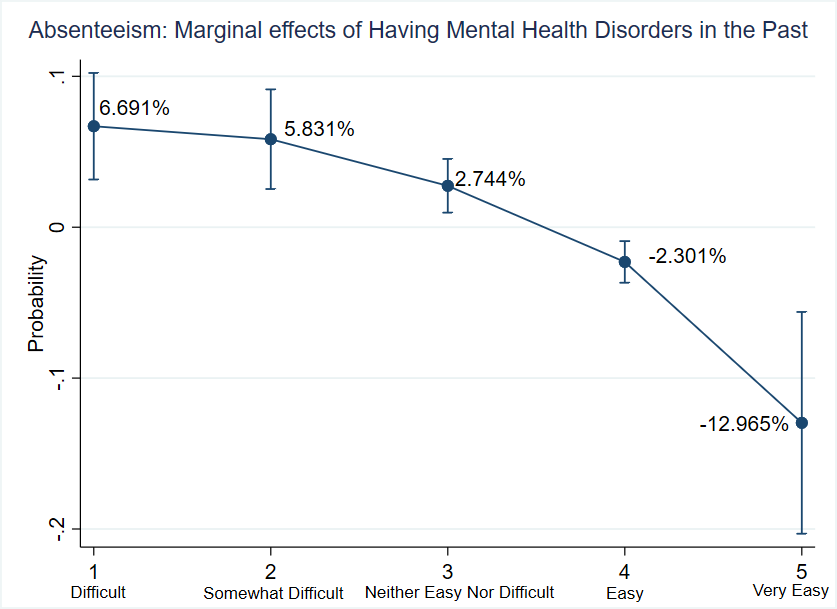

Regarding past experiences with mental health disorders, Figure 6 shows that, ceteris paribus, there is a 12.96 percentage point decrease in the probability of requesting leave very easily, while the probability of low levels of Absenteeism increases by 6.69 percentage points, suggesting an association between these variables. These findings seem to contradict the results presented by Verboom [18]. Recurrent exposure to mental disorders may be associated with increased difficulties in accessing medical leave as these requests become more frequent, which could contribute to lower levels of Absenteeism and potentially higher levels of Presenteeism, reinforcing the conclusions of Bayley [30] and Silva-Costa [31]

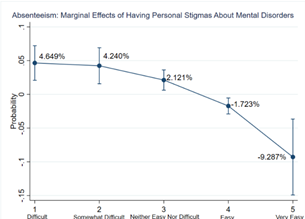

Figure 7 shows that, ceteris paribus, having personal stigmas around mental disorders is associated with raises of the probability of having the lowest levels of Absenteeism by 4.65 percentage points and decreases the probability of having high levels of Absenteeism by 9.29 percentage points. It implies that respondents internalize negative societal beliefs about mental health and feel ashamed to request leave for their mental health issues.

Figure 7: Marginal Effects of having Personal Stigmas about Mental Health Issues - Absenteeism Model.

Similarly, openness of individuals with co-workers and employers is associated with a higher likelihood of taking absences more frequently. Particularly, odds ratios showed that the probability that Absenteeism occurs 'Easy' or 'Very Easy' versus 'Difficult' or 'Very Difficult' is 55% higher when individuals talk freely with their employers and is 38% higher when they show openness with their co-workers.

Results suggest that individuals who discuss their conditions with others may exhibit a tendency to overcome personal stigmas around mental disorders and are more likely to request absence leaves to seek therapy. Finally, Table 8 shows that medical coverage of mental health services is associated with a 97% higher probability of finding absences 'Very Easy' and 'Easy' (versus 'Difficult' and 'Very difficult'). These findings suggest that access to insurance programs is associated with a higher likelihood of individuals seeking help when unwell and requesting leave to attend therapy sessions

5.2 Presenteeism Model Estimation

Table 10 presents the regression results for the Presenteeism model. Similar to the previous section, three models were estimated, incorporating controls for the survey year and the respondent’s state of residence. However, before delving into these results, Table 9 outlines the goodness-of-fit measures for the three ordered logit models compared to an ordered probit specification. As observed with the Absenteeism models, the ordered logit (ologit) specification outperforms the ordered probit (oprobit) in terms of sensitivity and specificity. This suggests that the proposed model provides a better fit for the available data. This finding aligns with expectations, given that the dependent variable of presenteeism exhibits distributional patterns that emphasize the tails (as shown in Figure 3).

In terms of performance, sensitivity across all models remains relatively low, ranging from 0.32 to 0.33, while specificity is comparatively higher, at approximately 0.81. These results suggest that the regressors primarily identify factors associated with a lower likelihood of employees experiencing higher presenteeism levels, even in the presence of mental health disorders. This outcome is particularly valuable for firms, as it provides insights to inform the efficient design of mental health programs, helping target resources to high-risk groups.

TABLE 9 - SENSIBILITY AND SPECIFICITY FOR PRESENTEEISM MODELS

| Model | Ordered Logit | Ordered Probit | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensibility | Specificity | Sensibility | Specificity | ||

| Model (1) | 0.2500 | 0.7500 | 0.3231 | 0.8131 | |

| Model (2) | 0.3218 | 0.8122 | 0.3227 | 0.8131 | |

| Model (3) | 0.3340 | 0.8182 | 0.3289 | 0.8171 | |

With the model characteristics discussed, Table 10 presents the regression estimates of the ologit specifications. It is important to highlight that all models have a Fraction of Missing Information close to 0.61, which means that 61% of the variability of the estimates is due to missing data. This shows that the FMI measure is particularly higher for Presenteeism than Absenteeism. The higher FMI for Presenteeism reflects the complexity of this variable, which captures personal perceptions of productivity changes that vary greatly across individuals. This variability poses challenges for inputting missing values effectively. While this does not invalidate the estimates, it introduces additional uncertainty, which should be carefully considered when interpreting the results.

Considering these characteristics, Table 10 presents the regression estimates. The findings indicate that statistically significant explanatory variables are associated with family history, access to workplace resources, past mental health disorder history, openness with family, unsupported response experiences, and the size of the respondent’s firm.

TABLE 10 - PRESENTEEISM (NON-TREATED) - ORDERED LOGIT REGRESSION RESULTS

*p<0.1; **p<0.05; ***p<0.01 Robust Standard Errors in Parentheses.

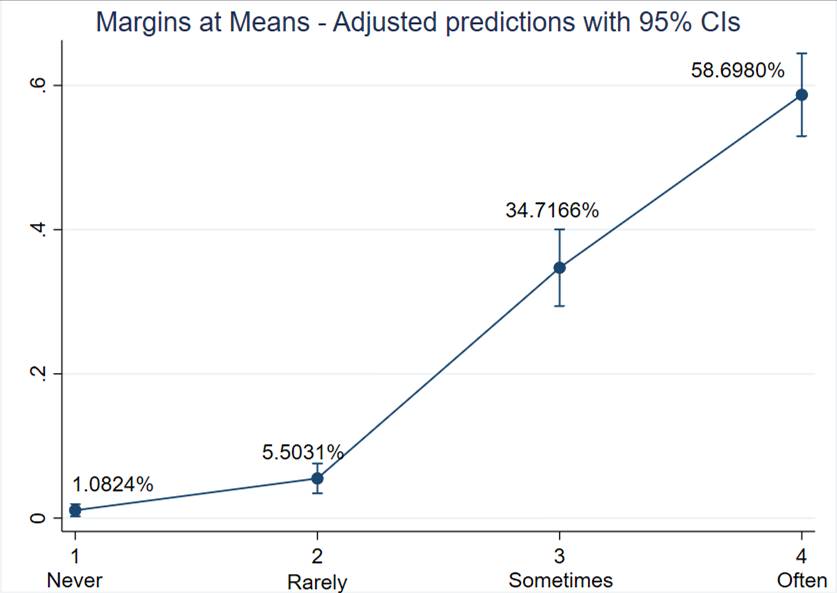

The estimates suggest that, based on the model, a person with an average profile-who has access to workplace mental health resources but is not open with their employer about mental health issues, has a relative openness score of 6.63 with family and friends, and has a personal or family history of mental disorders (see Section 3.2)-is estimated to have a 1.08% probability of not experiencing Presenteeism at work, a 5.50% probability of rarely experiencing it, and a 58.7% probability of often experiencing Presenteeism, as illustrated in Figure 8.

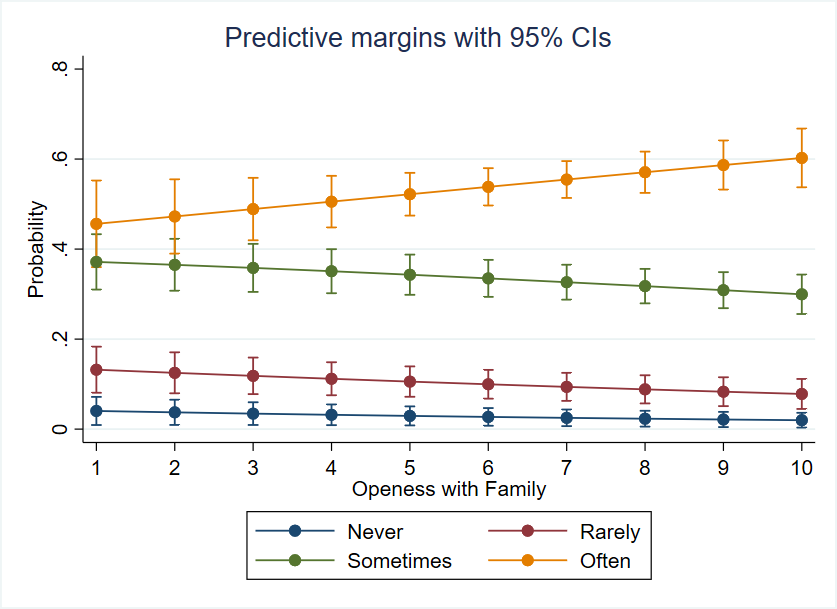

Similarly, ceteris paribus, estimates show that increases in an employee’s openness with family and friends are associated with a higher likelihood of experiencing higher levels of Presenteeism (thus reducing the chances of low Presenteeism), as illustrated in Figure 9. Specifically, odds ratios showed that, on average, the probability of experiencing Presenteeism episodes 'Sometimes' or 'Often' is 9% higher than experiencing them 'Rarely' or 'Never' when the grade of openness with family increases by one point. This finding aligns with the findings of Fiorini [32] and Vera-Calzaretta [33], where overwhelming family environments were linked to recurrent Presenteeism episodes. Nonetheless, over-reliance on family may lead individuals to use conversations with their inner circle as the primary outlet for addressing mental health issues, rather than seeking therapy. This potential confusion between openness and problem resolution could contribute to unresolved mental health issues and an increased frequency of Presenteeism episodes.

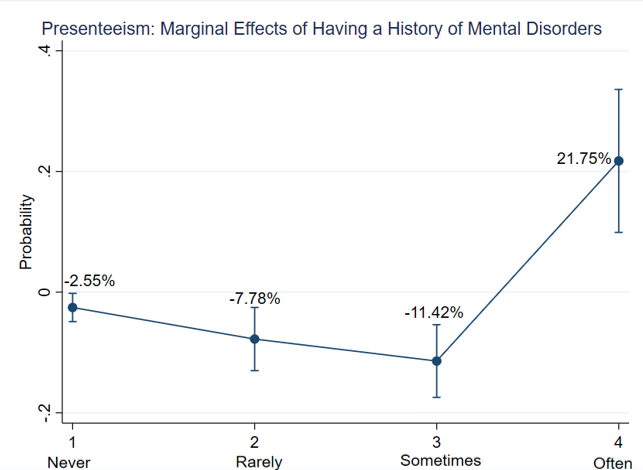

Additionally, ceteris paribus, having a history of mental disorders corresponds to a 21.75 percentage point increase in the probability of experiencing Presenteeism 'often.' Nonetheless, results in Figure 10 suggest that this increase may primarily reflect worse conditions for people who initially reported having Presenteeism episodes 'sometimes.' Consequently, individuals who did not experience Presenteeism when dealing with previous mental health disorders are not necessarily expected to face productivity losses at the workplace if they encounter future mental health issues.

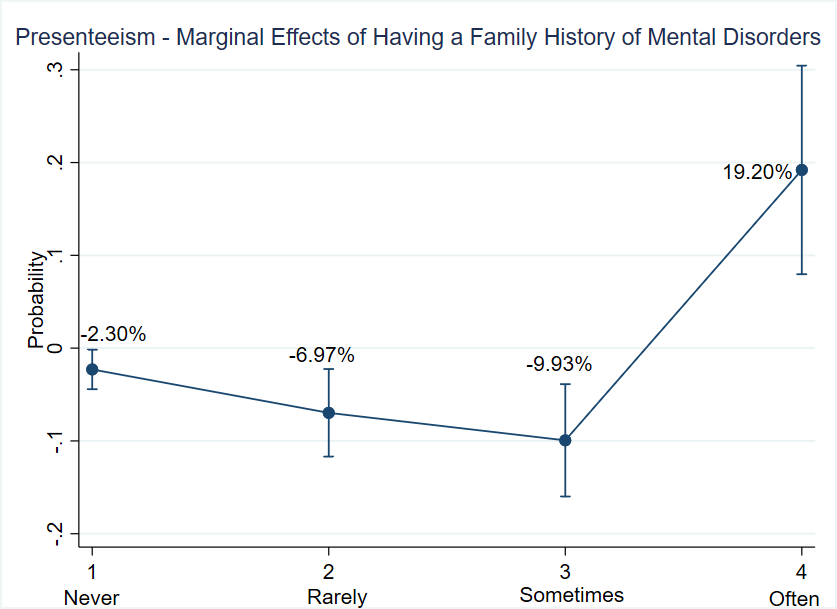

Equally important, Figure 11 demonstrates that, ceteris paribus, a family history of mental disorders is associated with a 19.20 percentage point increase in the probability of experiencing high levels of Presenteeism. Like the previous result, this increase appears to stem from worse conditions among individuals who initially exhibit moderate levels of Presenteeism. Specifically, the odds ratios indicate that, on average, the likelihood of experiencing Presenteeism 'often' or 'sometimes' is 2.64 times higher than the likelihood of experiencing it 'rarely' or 'never' for workers with a family history of mental illness. These results suggest support for the hypothesis that having family members with mental disorders may lead workers to internalize stigma and feel compelled to conceal their mental health struggles

In addition, access to workplace resources on mental health is associated with a 43.15% reduction in the probability of experiencing Presenteeism 'often' or 'sometimes' compared to 'rarely' or 'never.' Conversely, the probability of witnessing Presenteeism episodes more frequently is 2.51 times higher than experiencing them with less frequency when workers observe employers’ unassertive responses while dealing with subordinates’ mental health issues. Both findings align with the explanation proposed by Reenem [16].

Finally, the size of the firm where individuals are currently working also appears to be related to the variability in the levels of Presenteeism among individuals. Particularly, individuals working in large firms have a 57% higher probability of experiencing Presenteeism frequently (versus experiencing it 'rarely' or 'never'). As firms become larger, their control mechanisms are more sophisticated, making leave permissions harder to obtain, and workers face increased pressure to go to work while feeling unwell. This observation contrasts with the findings of Kensbock [25]

5.3 Presenteeism Model Estimation - The Effect of Getting a Treatment

Since one of the primary objectives of this study was to identify the key drivers and deterrents of Presenteeism, the previous subsection examined the perceived impacts on productivity when workers with mental disorders were not receiving therapy. Early access to mental healthcare services appears to be an important factor associated with reduced levels of Presenteeism. To explore the potential impact of receiving therapy on Presenteeism levels, the study analyzed respondents’ perceived levels of Presenteeism both when treated and untreated. Each respondent provided answers for both scenarios using the same measurement scale, creating a natural counterfactual for each observation in the absence of treatment. This approach facilitated the approximation of an Average Treatment Effect (ATE) through a simple before-and-after comparison, where the "treatment" refers to receiving therapy services (which varied among individuals and was not necessarily provided during the same period). The underlying assumption in this approach is that all therapy services are of equal quality.

The results were expressed in percentage terms by creating a binary variable (for both measures of Presenteeism) that equals one if the individual reported experiencing productivity losses due to mental disorders 'sometimes' or 'often.' The difference between these two binary variables was then calculated, and the average difference across all observations was reported as the general Average Treatment Effect of receiving therapy, as shown in Table 11.

TABLE 11 - ATE OF RECEIVING THERAPY IN PRESENTEEISM FREQUENCIES

| Variable | Imputation | N | Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATE | m=0 | 533 | -0.393996 |

| m=20 | 804 | -0.3681592 | |

| m=219 | 804 | -0.3880597 |

The results show a relative decrease in Presenteeism frequencies of 36-39% across all baseline levels. This suggests that therapy may be one of the most effective factors associated with reduced Presenteeism.

6. LIMITATIONS

The study has several important considerations to note. Firstly, it relies on self-reported data from the OSMI Survey, which introduces potential bias due to participants’ subjective perceptions and interpretations of their mental health experiences. Additionally, the cross-sectional design of the study restricts the ability to establish causality between variables, emphasizing the need for caution when inferring direct relationships. Moreover, the data collected spans from 2017 to 2021, suggesting that workplace dynamics and policies may have evolved since then, potentially affecting the relevance of the findings to current contexts.

Furthermore, given the wide variability in mental health conditions, the study may not comprehensively capture all relevant factors affecting individuals’ experiences, which can introduce omitted- variable bias. Variables such as employee’s job satisfaction, income levels, marital status may also significantly explain the Absenteeism and Presenteeism levels, and their exclusion may bias all the estimates of the model.

In addition, the study faces limitations when considering the context of Latin America and the Caribbean. Mental health challenges in this region are exacerbated by various factors that limit access to quality healthcare services, which may influence how employees perceive and report mental health issues at work, potentially affecting the accuracy of absenteeism and presenteeism measurements. Moreover, the diversity in healthcare systems and working conditions in the region means that findings based on U.S. data may not fully capture the unique dynamics of mental health in the workplace across different regions.

Lastly, the measurement of stigma within the study is acknowledged as inherently complex, as it may not fully encapsulate the diverse and nuanced experiences of individuals regarding mental health stigma in the workplace. These factors collectively underscore the need for nuanced interpretation and consideration of the study’s findings within the broader context of mental health research and workplace dynamics.

7. CONCLUSIONS

The findings of this study show the complex relationship between mental health disorders and workplace productivity. Particularly, it considered the study of Absenteeism and Presenteeism among U.S. tech sector employees. The analysis reveals several key insights into the factors that contribute to and mitigate these issues.

Firstly, the results confirm that a history of mental health disorders is significantly associated with a higher likelihood of both Absenteeism and Presenteeism. Employees with a history of mental health issues are more prone to experiencing difficulties in maintaining regular work attendance and often suffer from reduced productivity even when they are present at work. This suggests that past mental health challenges have a lasting impact on an individual’s ability to perform effectively in the workplace.

Moreover, the study finds that family history of mental disorders also plays a critical role in- creasing Presenteeism. Individuals with such a family background are more likely to experience mental health challenges themselves, which is associated with higher instances of Presenteeism. This finding highlights the importance of considering both personal and familial mental health history when addressing workplace productivity issues. In this regard, in regions like Latin America and the Caribbean, where socioeconomic conditions and access to healthcare services are more limited, these factors could have an even greater impact on employees.

Interestingly, the research also uncovers that personal stigma surrounding mental health issues is significantly correlated with higher Absenteeism. Employees who internalize negative societal beliefs about mental health are less likely to seek help or disclose their conditions, leading to increased Absenteeism as they may avoid work to cope with their issues privately.

Although the study has primarily focused on tech workers in the United States, the findings on absenteeism and presenteeism may have similar implications in Latin America and the Caribbean. This is because mental health conditions in that region are exacerbated by economic factors such as low budget allocation to mental health and the persistence of inadequate healthcare systems [8]. These social and economic challenges could lead to an increase in absenteeism and presenteeism levels in the region.

Therefore, it is essential that future research is not limited to high-income countries, such as the United States, where this study identified key factors, such as the impact of a prior history of mental disorders on productivity, the role of family history in increasing presenteeism, and the effect of personal stigma on absenteeism. It should also address the specific realities of regions like Latin America and the Caribbean. In consequence, these studies should analyze how socioeconomic and cultural factors in different regions influence absenteeism and presenteeism, contributing to the development of more inclusive and locally tailored intervention strategies. Moreover, a global approach would allow for the integration of diverse perspectives on workplace mental health, laying the groundwork for more effective research in labor contexts across various regions